Making Oneself at Home

by Alpesh Kantilal Patel

In relationship to the exhibition The World that Belongs to Us (TWTBTU), this essay weaves together my personal experiences, academic work, and engagement with the art world to discuss the idea of ‘making oneself at home’ and the fluidity of identity and belonging. My family traces its roots to Gujarat, India, and while I have lived most of my life in the United States, I was born in England, where I also completed my doctoral work. My first book, Productive Failure (2017), was partly borne out of trying to understand my complex ‘roots’ and ‘routes’ – the triangulated space demarcated by the US, UK, and Indian subcontinent.1 At the same time, my identification as queer and nonbinary adds traction to a simplistic mapping of my personal history onto this discursive space.

More specifically, each chapter of Productive Failure aimed to share a different iteration of what could be called a ‘queer transnational South Asian art history,’ the book’s subtitle. At the book’s core was an earnest interest in illustrating that there is always another story (a word I prefer to history because embedded in it is an element of fiction) to tell.2 In this book project, I mobilised queer as both a noun to signal the importance of sexuality to the overarching project and as a verb to destabilise our understanding of ‘transnational South Asia’. TWTBTU, as an exhibition, could allow us to think anew about what constitutes a queer transnational South Asian art history: this show assembles work by an intergenerational group of artists across countries with large South Asian populations – Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

I am particularly excited by this project as The New Art Gallery Walsall is near where I lived for the first four years of my life – in a house on Rooth Street in Wednesbury, England. Not surprisingly, I have very little recollection of that time, given my young age. My memories are a mixture of half-remembered lived experiences and imagined ones connected to photographs or anecdotes my family shared. According to Google Maps, the gallery is about a twelve to fifteen-minute drive from the house in which I lived. The house was sold in the 1990s by my grandfather when he came to live with my family in the United States. My nine cisgender heterosexual cousins, two aunts, and two uncles (all from my dad’s side of the family) are scattered across the Midlands, but a few still live relatively close to Wednesbury. When I lived in Manchester from 2005 to 2008 in my early 30s, I visited them a lot, and this was the first time in my life that I openly mingled with family as a queer-identified person. I have far fewer family members in the United States, and I never lived near any of them long enough to visit as consistently as I did in England.

The World That Belongs To Us, as an exhibition, could allow us to think anew about what constitutes a queer transnational South Asian art history…

1 Alpesh Kantilal Patel, Productive Failure: Writing queer transnational South Asian art histories (Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 2017).

2 In the anthology Storytellers of Art Histories (Intellect, 2022), my coeditor Yasmeen Siddiqui and I underscore the importance of ‘storytelling’ as a crucial part of the practice of those of us involved in the writing of the histories of art. Art histories materialize through the work of art historians and those of curators, archivists, and artists, as we highlight.

making oneself at home

Importantly, this notion of making oneself at home also materialises through another kind of kinship, not through bloodlines but shared interests in the visual arts and queerness. Indeed, the exhibition brings together queer-identified artists I have enjoyed getting to know or whose works I have become familiar with over the past two and a half decades.3 For instance, I did a studio visit with Salman Toor a year or two before his important Whitney Museum of American Art show in 2020 that brought his work to a larger audience. I had lived in New York City for eight years in my twenties, but this was perhaps the first time I had seen figurative paintings depict the lives of queer brown people. It was not only the subject matter that was of interest, though; it was his stylistic reference to a host of canonical Western art history. In the New York Times, American art critic Roberta Smith titled her 2020 review of the Whitney show “Salman Toor, a Painter at Home in Two Worlds.”4 Only two? I felt like she missed the point of his works: Toor’s world-making is incessant and multiple.

Chitra Ganesh’s 2022 animated work Before the War, part of TWTBTU, explicitly references the planetary, constellations, and the cosmological, even as she grounds her film in climate change and ongoing earthbound human strife. I met her in New York City in the late 1990s, have written about her work, and included her Queer Power: A Time Travelling Coloring Book (2021) in an exhibition I just organised in New York City.5 She is the first queer-identified artist of South Asian descent I met, but what I have most cherished about my friendship with Chitra is that it has made clear to me that there is endless multiplicity, difference, and variety within queer transnational South Asian subjectivities. In fact, ‘diversity and difference’ and ‘beginning of diaspora’ appear as printed text on the photograph, part of the 1992 series Changing Spaces of another exhibiting artist Roshini Kempadoo, whom I have not met. While the work is not explicitly about LGBT*Q identity, I am moved by this series’ poignant focus on mixed-race couples.6

“I consider the works on display less as representations of transnational South Asian identities than as active agents bringing into being the notion of home as always in process and protean.”

Chitra Ganesh’s, Before the War, 2022. Still from animation. Copyright the artist.

Indeed, while I have not had the pleasure of meeting all of the artists in the show, their works resonate with me in powerful ways, reaffirming my South Asian-ness as always in a state of becoming. So, while the notion of ‘home’ is connected to my roots, routes, and sexuality, I theorise it here as a feeling equivalent to perpetual mutability and change. Art historian Marsha Meskimmon, in her conversation with Marion Arnold, powerfully notes that ‘positioning movement, process and becoming (rather than being) at the centre of the concept of “home” suggests that making oneself at home in the world is never fixed or finished and also that the “self” and “home” are mutually emergent’.7 In this way, I consider the works on display less as representations of transnational South Asian identities than as active agents bringing into being the notion of home as always in process and protean.

3 I have met Salman Toor, Chitra Ganesh, and Sa’dia Rheman in person, all of whom I discuss in this essay. I have not met Jagdeep Rana, Charan Singh, or Sunil Gupta, but am familiar with their works. I conducted an unpublished interview with Singh in 2017, and I wrote a short personal reflective statement about Gupta’s work: ‘Sunil Gupta’, in Art after Stonewall:1969 to 1989 (exhibition catalog), edited by Jonathan Weinberg (Columbus Museum of Art: Ohio, 2019), 46.

4 Roberta Smith, ‘Salman Toor, a Painter at Home in Two Worlds’, New York Times, December 23, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/23/arts/design/salman-toor-whitney-museum.html

5 “Form and Formless,” UrbanGlass, Brooklyn, October 2023-February 2024, https://urbanglass.org/events/detail/form-and-formless. I have written about Chitra’s work here: “Chitra Ganesh at Rubin Museum,” Artforum 57, no. 2 (October 2018): 232 and “The Art of Queering Asian Mythology,” in Global Encyclopedia of LGBTQ History: A-F, edited by Howard Chiang (New York City: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2019), 127–34.

6 I did not have the opportunity to engage with Kempadoo’s most recent work in time for the writing of this essay, but I am looking forward to engaging with it.

7 Marion Arnold and Marsha Meskimmon, ‘Making Oneself at Home’, Third Text (29: 4-5): 256-265, DOI: 10.1080/09528822.2016.1155327.

multiple and One

In my afterword to Productive Failure, I began to muse on how my entire book was about ‘a constant reassessment of belongingness’. I wrote that the ‘need or longing to belong is powerful but to what one belongs is best thought of as “multiple and One” per Édouard Glissant.’8 For him, the geological formation of the archipelago—a series or chain of islands scattered across a body of water—became a potent analogy for conceptualising identity: each island is autonomous while still part of the larger group of islands. Glissant believed creolisation and the archipelago went hand in hand. As a body of thought, creolisation is connected to the unequal power relations and violent history of the Caribbean in which colonialists lived in a shared space with slaves, indentured servants, and their descendants. In her book Creole in the Archive: Imagery, Presence and the Location of the Caribbean Figure, Kempadoo powerfully conceptualises a ‘creole archive as a central creative and primarily visual prism through which to explore the image, presence, location and representation of the Caribbean figure’, a term she uses to conjure a ‘metaphorical presence of subjectivities (which at times may be considered ghostly), associated with the Caribbean and more specifically Trinidad.’9

Glissant believed that creolisation could be applied to thinking outside of the Caribbean. For instance, in a grand and poetic gesture, he applied what he refers to as ‘archipelagic thinking’ to the world, which he writes is ‘becoming an archipelago and creolising’.10 If we consider creolisation as a process that results in continuous entanglement and constant renewal, then I argue that each point of renewal is not a moment of hybridisation but instead connected to active home-making that cannot be traced back to discrete components. Therefore, I cannot be reduced to roots, routes, or queerness. Instead, I am building a home wherever I go: indeed, the title of the exhibition, ‘The World that Belongs to Us’, implies as much.11

8 Patel, Productive Failure, 211 (both quotes).

9 Roshini Kempadoo, Creole in the Archive: Imagery, Presence and the Location of the Caribbean Figure, (London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Incorporated, 2016). Accessed November 9, 2023. ProQuest Ebook Central.

10 Édouard Glissant, Traité Du Toute-Monde (Paris: Gallimard, 1997), 193-94.

11 Mimi Sheller would refer to this as ‘achieved indigeneity’. She writes, ‘Creolization (becoming Creole) can therefore be understood as a process of achieving an indigenous status of belonging to a locale through the migration and recombination of diverse elements that have been loosed from previous attachments and have reattached themselves to a new place of belonging’. See Mimi Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean: From Arawaks to Zombies (London; New York: Routledge, 2003), 182.

building networks and queer Asian worlding

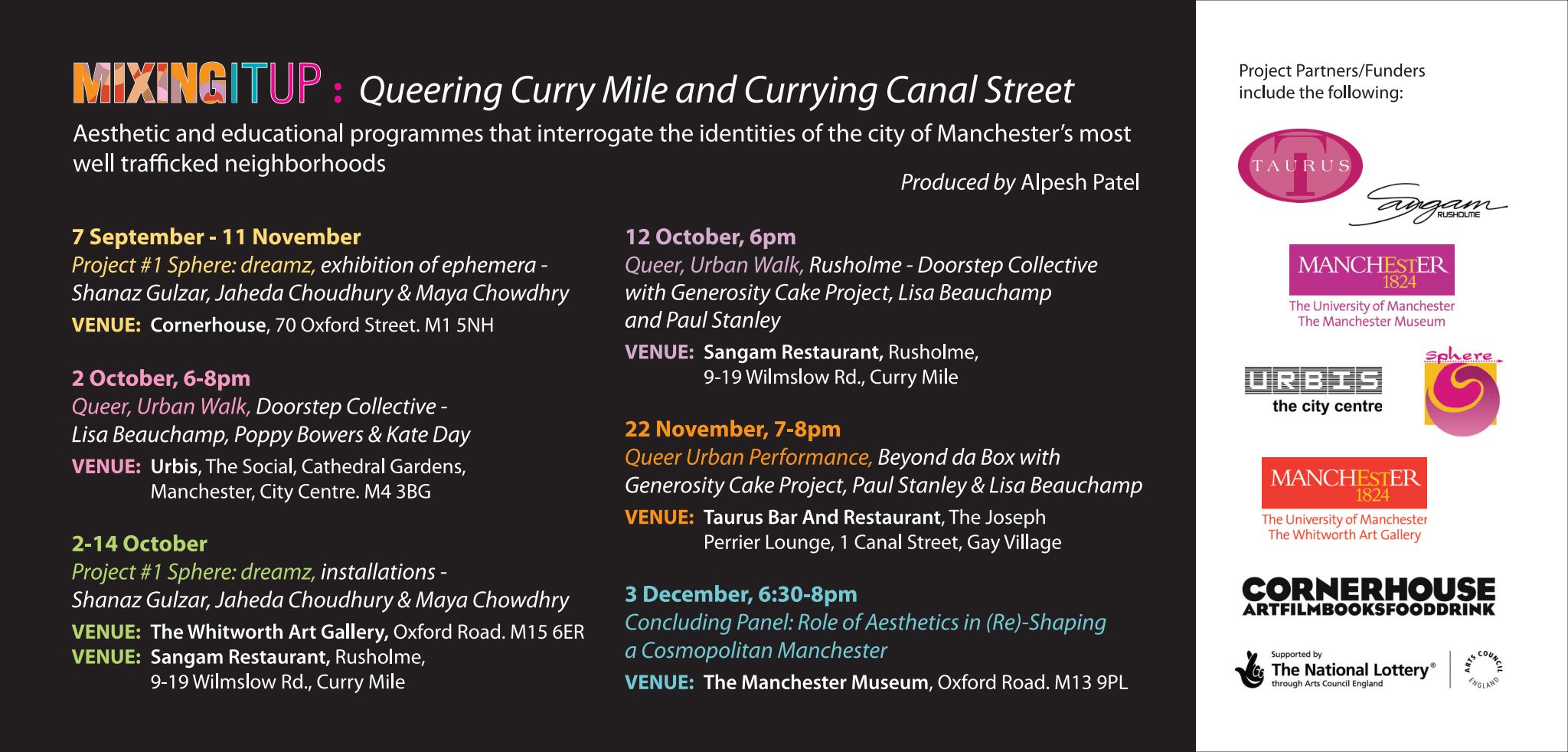

TWTBTU is as much about homemaking as it is an example par excellence of networks of friendships and connections across geographies. I want to share here a bit about my new book project and how it, too, is indebted to such networks and by extension the building of bridges to instantiate queer Asian worlding. Indeed, one chapter focused on queer Asian voguing material culture across nations began to coalesce partly because of the invitation to write this essay. To explain, my first instinct in researching was to reconnect with my friend Jaheda Choudhry, a Muslim and lesbian-identified artist who grew up and lives in northwest England. I co-produced an exhibition with Choudhry, ‘Mixing It Up: Queering Curry Mile and Currying Canal Street,’ in the Autumn of 2007. Created by Manchester-based art and music collectives based on my conception of using culture to subvert, confuse, or ‘mix up’ the production of a rationalized Manchester – and thereby (I hoped) potentially shift expectations about the people generally found in Curry Mile, known for its many South Asian restaurants, and the Gay Village, so named for its many queer restaurants and clubs – the public art projects I commissioned for ‘Mixing It Up’ took place in these two areas of the city. It had been a decade since I had spoken with Choudhry. When I got a hold of her, she explained she now works as a dresser for the voguing ball scene in Manchester and is directly involved in House of Spice. Houses are kinship structures outside of bloodlines, and voguing is an identity-affirming practice and can be traced back to drag ballroom culture.

Postcard (back) for exhibition Mixing It Up: Queering Curry Mile and Currying Canal Street, Manchester, 2007, with a schedule of events

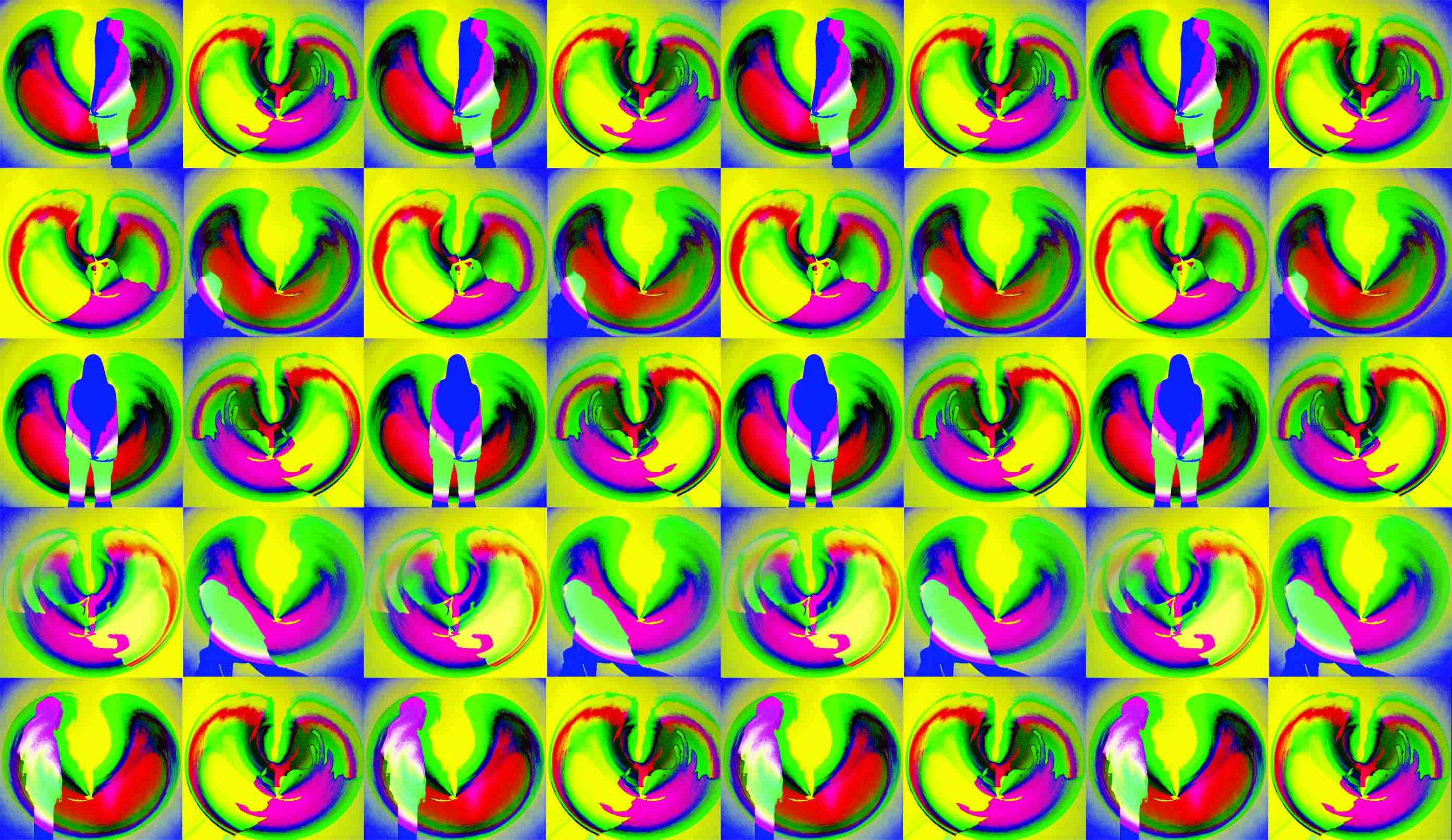

Sphere, Untitled (wall mural), Cornerhouse, Manchester, England, September to November 2007. Commissioned for the exhibition Mixing It Up: Queering Curry Mile and Currying Canal Street, 2007

Ballroom culture has since reached many corners of the world, including East Asia. Curator and friend Abby Chen, with whom I have collaborated on a queer Chinese feminist exhibition that included voguing, has invited me to speak at a symposium on islands and archipelagos connected to her curation of Taiwan’s pavilion at the next Venice Biennial. The ‘tongzhi’ voguing community of Taipei has been characterized as ‘beyond doubt the major embryo for voguing in Asia, which nourished the seeds and spread them around’ by the cultural critic Quilla Chau in the online magazine Lifted (2022). The term tongzhi (同志, comrade, or LGBTQ people) was first used in Hong Kong but was quickly appropriated by Taiwanese academics to rebrand the gay community to align with socially accepted standards to gain mainstream approval.

Finally, last summer, art historian and friend Przemysław Strożek in Poland informed me of a fascinating exhibition of the clothes of Andy Nguyen (1963-2018), a Polish drag queen of Vietnamese origin, in Warsaw, Poland. I spent several months living in Poland in 2015 and 2016, exploring transnational approaches to LGBT*Q artistic practices there. The Law and Justice (PiS) Party took over when I was there. During their first year in power in 2015, the new government immediately began xenophobic moves such as staunchly refusing to comply with European Union quotas for refugees, primarily from Syria and other conflict areas. At the same time, Poland has increasingly become visibly more homophobic. At one point, over one-third of Poland was deemed an ‘LGBT-free zone’.12 Despite the above, Poland becomes a site that provides a space for a drag queen of Vietnamese descent to be admired, loved, and accepted as Polish.

What I want to emphasise is that the possibility of an international investigation of queer Asian-ness through material culture is routed through my personal, shared, embodied connection to a web or network of queer familial relationships with a wide-ranging group of curators, artists, and friends.TWTBTU is itself a manifestation of the kind of kinship I describe above.

Installation images of exhibition Kim Lee: Queen of Warsaw, Wola Museum, Warsaw, 2023 Photos by Marcin Sieczka © Muzeum Warszawy

Installation images of exhibition Kim Lee: Queen of Warsaw, Wola Museum, Warsaw, 2023 Photos by Marcin Sieczka © Muzeum Warszawy

shall and shoal: a creolizing moment with Sa’dia Rehman

I want to conclude by returning to the context of the exhibition. Coincidentally, one of the artists in the show, Sa’dia Rehman, was taking part in a residency in Philadelphia, where I currently live. We have been trying to meet for some time. First, the pandemic got in the way, and then our schedules never seemed to align. When I finally sat down with them at a coffee shop in the city centre, it was Monday, October 9. It was two days after the horrific massacre of Israeli citizens by Hamas but before the brutal bombing campaigns of Gaza had begun. Like many, I was anxious and feeling a mix of emotions. But when I saw Sa’dia, my anxiety started to wane. I felt very much at home with them despite having never met. While sipping our coffee, we talked about many things, including what was happening in Israel and Palestine.

One memory that sticks out is a sketch they showed me of the work they planned to bring to fruition at The New Art Gallery Walsall. It included representations of a fruit that Sa’dia would explain were mangoes. They explained that their father fondly recalled the plethora of mango trees that were part of the village’s landscape that the creation of the Tarbela Dam has since erased. It was a wonderful memory for them amid a general sense of intergenerational trauma. When they began speaking of mangoes, my mind went to living in Florida in the 1980s when my family visited my dad’s cousin’s family in Fort Pierce. My uncle took us to a farm where we procured fresh mangoes. I loved the possibility of Sa’dia’s work taking me to this memory – something that they, of course, could never have imagined.13 The above was a creolising moment of homemaking, engendered by a mere sketch of a work that had not been realized yet. It also made me empathise more easily with a history I knew little about: Sa’dia’s father’s home in Khar Kot, near the Indus River in northern Pakistan, was one of around 184 villages destroyed by the dam that displaced more than 100,000 people.

In fact, worth noting is that in their proposal for their site-specific installation, Sa’dia mentions that through conversations with the exhibition curators, they became aware that there is a large Mirpuri Muslim population in the West Midlands that is the direct result of the production of another dam – the Mangla Dam– by the Pakistani government and the World Bank in the 1960s.13 It is the world’s largest. The bird in flight with packages in their installation at the museum is inspired by drawings from the artist Sabba Khan, who traces her family back to this longer extant place and with whom Sa’dia got to have ‘jovial conversations’. In my mind, I imagine them both sitting in a coffee shop, too. While they both for sure had very different conversations than what I had with Sa’dia, they similarly forged familial bonds laying the foundation for queer homemaking.

Sa’dia Rehman, and now we must roam…, 2023, site specific installation; blackboard paint, chalk, plaster gauze, ink. With thanks to Greater Columbus Arts Council funding. Commissioned by The New Art Gallery Walsall as part of group exhibition The World that Belongs to Us, 24 November 23 – 9 June 24.

My point here is that the notion of making oneself at home that, I argue, is woven through The World that Belongs to Us entails a shift in our thinking from the notion of an autonomous, transcendent individual who does the ‘making’ to thinking about the processes by which both the ‘self’ and the ‘home’ are materialised. Doing so emphasises intersubjectivity and connections with/in the world and reminds us that this is a material process, a making from here, from the residues and sedimented traces of the (often violent) past through which a more ethical future shall unfold: and I believe this is what the show promises us.

I am using the word ‘shall’ purposefully here. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, it connotes ‘a command, promise, or determination’. Curiously, when I typed ‘shall’ into the search field, the OED also brought up the word ‘shoal’, which is described as ‘a variant of shall’. Given the context of Sa’dia’s work, I found this generative: to explain, a shoal is a ‘place where the water is of little depth’. If dams increase the water level to generate electricity – and, in their creation, destroy homelands – then one imagines there is no better metaphoric place to be than a shoal. One could characterise my sentiment as naïve, but I believe that the visual arts and even art historical writing can be powerful for showing us where we have been, where we are, and where we could be. I imagine a time and place where mangoes grow generously and unfettered.

12 Many thanks to Sa’dia for sharing the following article through which I learned so much more about mangoes: Ahmed Ali Akbar, “Inside the Secretive, Semi-Illicit, High Stakes World of WhatsApp Mango Importing,” Eater, August 12, 2021. (accessed November 19, 2023)

13 My thanks to exhibition Aziz Sohail for sharing Sa’dia’s written proposal. And my thanks both to them and the Head of Exhibitions Deborah Robinson for generously inviting me to write this essay and being so patient with me.

Biography

Alpesh Kantilal Patel is an associate professor of global contemporary art history at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art and Architecture and Curator at Large at UrbanGlass, Brooklyn, where they organize exhibitions under the theme: forever becoming: decolonization, materiality, and trans* subjectivity. Their influential work includes Productive failure: Writing queer transnational South Asian art histories (2017) and co-edited publications, Storytellers of Art Histories (2022) and Curatorial Impacts – The Futures of Okwui Enwezor (2021). They are working on a new monograph, Multiple and One: global queer art histories, under contract with Manchester University Press, and the anthology Creole Archive: Jacek Kolasinski. With a background in curatorial and administrative roles at institutions like the Whitney Museum and the New Museum in NYC, Patel earned their doctorate from the University of Manchester after graduating from Yale University. They are currently Chair of the College Art Association’s flagship publications Art Journal and Art Journal Open Editorial Board.

Bibliography

Publications (select)

Patel, A. (2017). Productive failure: Writing queer transnational South Asian art histories. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Patel, A. & Siddiqui, Y., eds. (2022). Storytellers of Art Histories: Living and Sustaining a Creative Life. Bristol: Intellect Books

Patel, A., Davidson, J.C. & Okeke-Agulu, C., eds. (2021). ‘Curatorial Impacts – the Futures of Okwui Enwezor’. Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 48(1).

Articles and Essays (select)

Patel, A. (2023d) ‘Reflecting on Whiteness in Recent Contemporary Artwork Exploring Transnational Poland’, Pp. 363-373 in Tatiana Flores, Florencia San Martin and Charlene Villaseñor Black (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Decolonizing Art History. London: Routledge.

Patel, A. (2023c) ‘Post/Anti/Neo/De-Colonial Theory and Visual Analysis’. Pp. 311-326 in Amelia Jones and Jane Chin Davidson (eds.). A Companion to Contemporary Art in a Global Framework. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

Patel, A. (2023b) ‘Queer and Trans/Joy Worlding’ and ‘Disorderly Encounters and Irregular Connections: Towards Cruising’. For the exhibition Self, Contemporary Craft, Pittsburgh, PA.

Patel, A. (2023a) “Didier William at the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami.” Artforum 61(8), 171.

Patel, A. (2021). “Queer Chinese feminist Archipelago: Shanghai, San Francisco, and Miami,” philoSOPHIA: A Journal of transContinental Feminism 11(1), 194-212.