Karen McLean

Ar’n’t I a Woman!

The New Art Gallery Walsall

18 February – 3 July 2022

Karen McLean’s exhibition A’rn’t I a Woman! should have opened at The New Art Gallery Walsall on 1 May 2020. Sadly it was delayed due to the pandemic but Karen did get to show some of the work at Block 336 in Brixton, London in May/June 2020. We are delighted to finally be able to open the exhibition in Walsall, in the space the work was designed for.

This exhibition guide/microsite contains two specially commissioned essays by Gill Perry and Emily Zobel Marshall. It will be updated further with documentation of the exhibition in Walsall.

Weaving Bodies

by Gill Perry

Just before sunset an agent bought her for two hundred and twenty-six dollars. She would have fetched more but for that season’s glut of young girls. His suit was made of the whitest cloth she had ever seen. Rings set with coloured stone flashed on his fingers. When he pinched her breasts to see if she was in flower, the metal was cool on her skin. She was branded, not for the first or last time, and fettered to the rest of the day’s acquisitions.

(Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad)1

Over the last few decades writers and feminist historians have been researching the everyday lives of enslaved women, expanding a history long dominated by the literature on male experience in the periods of antebellum and Caribbean slavery. As Deborah Gray White wrote in her ground-breaking book Ar’n’t I a Woman? first published in 1985: ‘Slave women were everywhere, yet nowhere’.2 Coulson Whitehead’s powerful novel The Underground Railroad explores some of this hidden history as he tells the harrowing story of Cora, a ‘runaway’ on a plantation in Georgia who makes the courageous decision to escape with a fellow slave Caesar to the north. The gruelling experiences and life choices of enslaved women are mediated through Cora’s intensely physical, part fictional journey. As her story reveals, enslaved women’s bodies were exploited both in the plantation fields and through sexual violation. Karen McLean’s recent art installations make vivid use of metaphor and semiotically charged objects to explore some parallel experiences, especially the important role of the body in both the representation and resistance of enslaved women or ‘bondwomen’.3

Born in Trinidad in 1959, she currently lives and works in Birmingham. Over the last decade McLean has consistently researched and referenced her Caribbean past in evocative installation works concerned with issues of identity, ‘home’ and post-colonial cultures (see, for example, her series Primitive Matters, 2010). This exhibition reveals her on-going interest in the history, folklore and material cultures of Caribbean colonial history, and its close relationship with the history of slavery in the antebellum South. Her on-going interest in the roles of women within those histories is evident as she draws on a long tradition of female weaving, stitching and dyeing of fabrics. These are some of the gendered activities that were also deployed by bondwomen in their attempts to control commercial and social processes.4 Through her mimicry and aestheticisation of such processes, McLean has constructed a multi-layered installation project that invites a contemporary audience to engage with a hidden history of women’s suffering and resistance.

1 Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad, (New York: Doubleday, 2016), p. 5.

2 Deborah Gray White, Ar’n’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1985), p.23. See also the influential research on this theme by Barbara Bush, Slave Women in Caribbean Society 1650-1838 (Kingston: Heinemann Publishers, 1990).

3 ‘Bondwomen’, a term originating in the 14th century, is increasingly used by researchers as an alternative to ‘female slaves’ to describe women bound to labour without wages. I am using both terms in this essay.

4 There is a growing literature on the culture of resistance among bondwomen. Useful texts include: Stephanie M.H.Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (University of North Carolina Press, 2004); Loucynda Jensen, ‘Searching the Silence: Finding Black Women’s Resistance to Slavery in Antebellum U.S. History in PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal, Vol 2:Iss 1, Article 23, 2006; Hilary McD. Beckles, Natural Rebels: A Social History of Enslaved Black Women in Barbados, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1989).

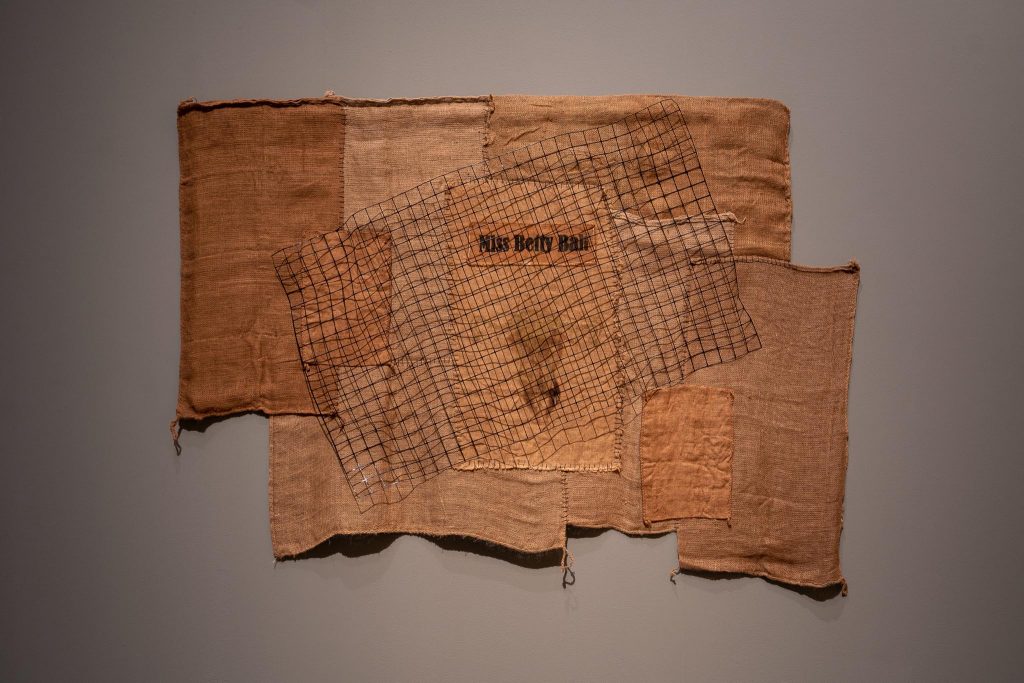

The branded, printed and stitched sacks of her two wall hangings Woven Bodies 1 and 2 are replete with corporeal and symbolic references to the harsh lives of enslaved women, re-presented here as iconic figures, celebrated within a patchwork of hessian sacks. These allude to the commercial history of slavery; hessian is an ancient material derived from jute and is famously durable. Such sacks were used to carry produce from the plantations, such as sugar, coffee and tea; they were the vehicles of distribution to the colonial capitals and symbols of the accumulation of wealth that ensued. McLean sourced hers from various modern suppliers, including ebay, Brick Lane and an outlet in Hastings, combining different textures, tones and weaves. Each was dyed using tea and coffee, turned inside out to hide the old lettering, and cut in half. She then stitched on new hessian backs, creating her own reclaimed and recoloured sacks, imbued with laborious practices that echoed those of the past. Imitating the gendered activities of dressmaking and quilt-making in enslaved societies, she laced them together with animal suture thread, another corporeal reference to the wounded/sutured bodies of enslaved people, especially women. As Entela Bilali has argued: ‘The weaving of stories into quilts became a way for Black women to defy the system of slavery and patriarchy and assert themselves …. Black women weaved resistance into their daily lives.’ 5

Blood Alley, c 1930, © PLA Collection/Museum of London

This photograph was taken at the North Quay, West India Docks and shows a gang of dockers trucking bags of sugar beneath an awning of washed sacks that are hung out to dry. ‘Blood Alley’ was the nickname given to roadway between the transit sheds and sugar warehouses because handling the sacks of sticky West Indian sugar badly chafed and cracked the dockers’ skin.

Woven Bodies 2, 2020, 150 x 240 cm, hessian sacks, screen prints, branding, animal suture thread, aluminium wire mesh. Courtesy the artist and The New Art Gallery Walsall. Photo: Mark Hinton.

…sacks were used to carry produce from the plantations, such as sugar, coffee and tea; they were the vehicles of distribution to the colonial capitals and symbols of the accumulation of wealth that ensued.

Two haunting, statuesque images of women, one wielding a machete and the other holding an abeng (animal horn)6 are repeated across the larger wall hanging. Both are composite images representing the iconic Queen Nanny of the Maroons. The Maroons were originally escaped enslaved people who ran away from their Spanish-owned plantations when the British took the Caribbean island of Jamaica from Spain in 1655.7 Queen Nanny or Nanny of the Maroons led a community of former enslaved Africans called the Windward Maroons, and is now a celebrated figure in Jamaican history. During the early 18th Century the Maroons fought for many years against the British colonisers and terrorised British troops, until a peace treaty was signed in 1740.8 Drawing on multiple sources including a portrait on the Jamaican 500 dollar banknote and a sculpture of Nanny in the National Hero Park in Jamaica, McLean has woven together various physical characteristics and metonymic objects (such as the distinctive headwrap and abeng), into two single figure studies. They are presented as powerful symbols of local resistance, printed in black onto dyed sacks in a celebratory repetition of their struggles. McLean grew up saturated in Caribbean folklore in which myths of the Jamaican Nanny resonated across then newly independent islands such as Trinidad and Jamaica (both achieved independence in 1962). Moreover, Nanny’s symbolic status as a figure of anti-colonial struggle was inseparable from her gender: she was consistently claimed as the brave mother of resistance against slavery. These powerful mothers of resistance can be seen to contribute to a rich and evolving artistic tradition. Goddesses, witches and uncomfortable feminine archetypes have been reappropriated by some of the best-known feminist artists working in Europe and the USA over the last four decades, including Nancy Spero, Carollee Schneemann, Louise Bourgeois and Cindy Sherman.9 McLean has appropriated this tradition to re-insert the enslaved black woman into a real and symbolic setting. Her statuesque Nannys are composite female archetypes, celebrating a (partly) lost history of women’s resistance to slavery.10

5 Entela Bilali, ‘The Art of Quilting in Alice Walker’s Fiction’, The 2nd International Conference on Research and Education – Challenges Towards the Future (ICRAE2014), 30-31 May 2014, University of Shkroda, Albania. ISSN: 2308-0825.

6 An abeng is an animal horn and musical instrument used by the Akan people. It is often to be found in Jamaica where it is associated with the Maroon people.

7 The Spanish called these free slaves ‘maroons’, derived from the word cimaroon which means fierce or unruly. The Jamaican Maroons occupied a mountainous region of deep forests known as the Cockpit, where they constructed crude fortresses and followed cultural traditions derived from Africa and Europe. The figure of ‘Nanny’ (usually without a definite article) reputedly originally came from Ghana. Although there is little surviving information about the origins and activities of Queen Nanny, some useful research has been done by Karla Gottlieb and Mario Azevedo. For a summary see https://www.eiu.edu/historia/Eberle2017.pdf

8 See Mavis Christine Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 1655-1796: a history of resistance, collaboration & betrayal. 1990 (Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press), and Lucille Mathurin Mair, The Rebel Woman in the British West Indies during Slavery (University of the West Indies Press, 1995)

9 For a fuller discussion of this issue and the symbolic potential of women’s bodies, see my catalogue essay ‘Witches, Housewives and Mothers: Crossing (Irish) Borders in the Body Politic’, in Fionna Barber (ed), Elliptical Affinities, Highlands Gallery, Drogheda, 2019-20, pp. 18-27.

10 As such these Nannys might also be seen to contribute to a reclaiming of the visibility of black women within history and mythology. For example, Maud Sulter’s series Zabat (1989), a series of photographs of black women posing as the nine muses of mythology. See for example Urania in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery (https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/48638).

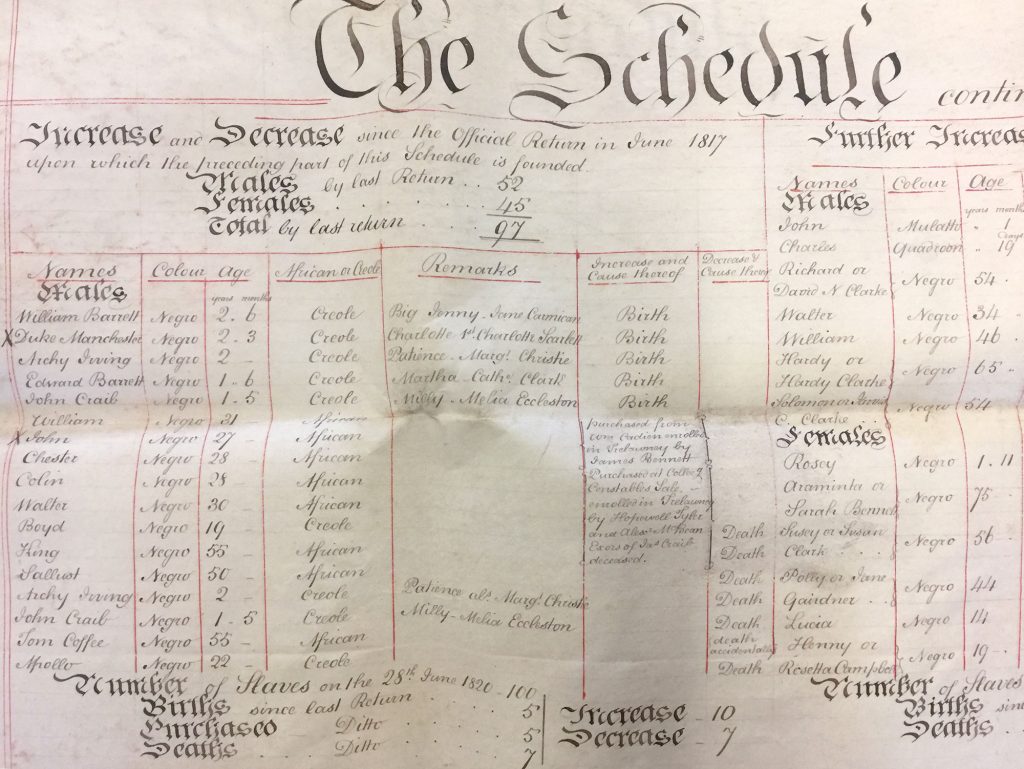

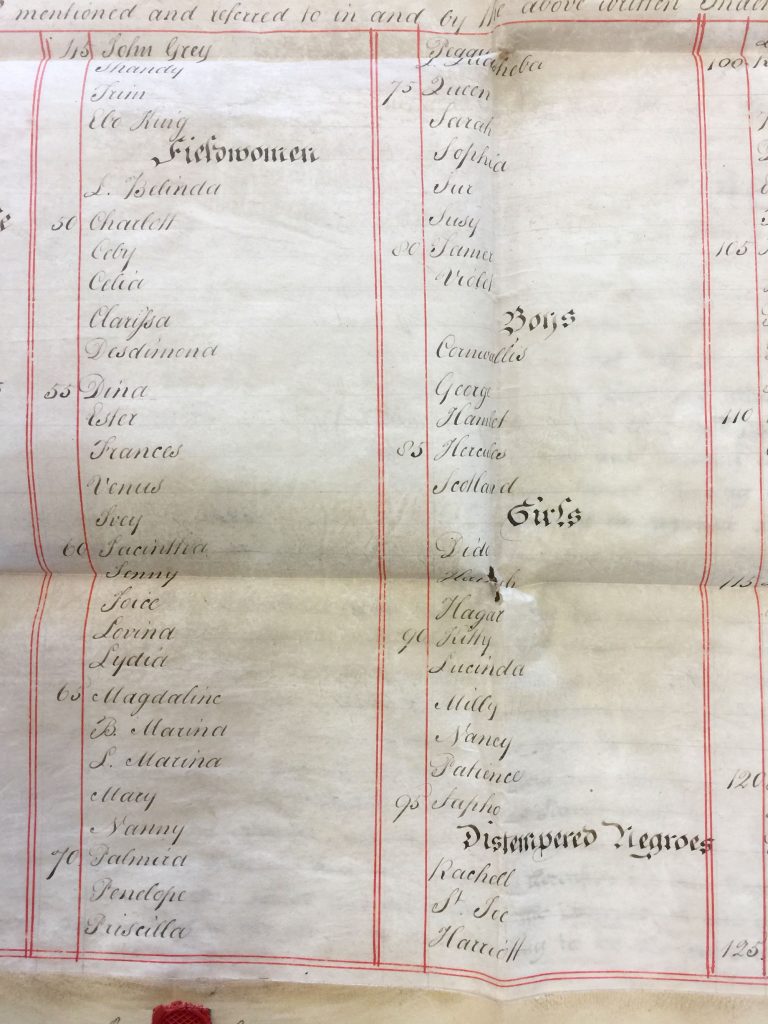

Naming is another means of controlling and defining a workforce. Researching in the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton, McLean found indentures from the Gale Plantation, in which enslaved people were listed by first names (as male or female, distempered, midwives, boilers, etc.) as part of the owner’s chattels. This listing usually included the designations negro, ‘mulatto’, or ‘Quadroon’ according to the perceived degree of black or white; ethnicity was described as ‘African’ or ‘Creole’. From these she selected the names printed above the wombs, which resemble decorative shapes scattered across the hanging sacks. All are printed in Helvetica Neue, a popular typeface on the original plantation sacks and a signifier of their commodity status. Many bondwomen were given anglicised names (such as Sophia, Charlotte, Grace, Priscilla, Esther) as part of their absorption into colonial culture and eradication of African heritage. Some others retained their African names, or hybrid versions (such as Phibbah, Betty Bah), an indication, perhaps, of resistance to acculturation. The black, shadowy shapes of the wombs in McLean’s work are achieved through a process of branding, echoing both the violent physical abuse (of the branding iron on the body) and ‘ownership’ involved in the trade of enslaved people. Yet she seeks to reinstate some status originally denied to her subjects by adding the prefix ‘MISS’ – a title denied to black women – to her names, and by screen printing the uterus in gold onto the sackcloth. Expensive and coveted, gold helps to reframe the terms of this seemingly coarse patchwork hanging and the objects that surround it.

Female reproduction was itself an important source of value; it insured an ongoing source of income for the plantation owners, hence the smaller sacks that McLean has stitched onto the wall hanging. These break the lines of stitching and reference the ubiquitous hessian sacks, some of which would have contained dead babies (whether stillborn, aborted, or from infanticide).11 The desire to control women’s reproductive and sexual functions was part of the ethos of colonial and antebellum enslavers. As Stephanie Camp has argued, ‘the slave body, most intensely women’s, served as the “biotext” on which shareholders inscribed their authority and indeed their very mastery.’12 Yet women’s reproductive capacities were also often deployed by bondwomen as a means of resistance.13 McLean mediates this resistance through her use of crude hessian quietly embellished with glitter, shining with double meaning.

Silence me not…me ah rise, 2020, hessian, screen prints, branding, cowrie shells, 18 and 22 carat gold plated beads, gold waxed thread, brass, acrylic.

Courtesy the artist and The New Art Gallery Walsall. Photo: Mark Hinton.

Other objects heavy with historical meaning, also adorn – or impinge upon – the sacks. Wire mesh obscures our view of the smaller wall-hanging (Woven Bodies 2) as it references the fettering of enslaved communities and constraints on women’s freedom. In contrast, small cream-coloured cowrie shells form delicate trails suggesting ovaries on Woven Bodies 1, and rattle gently below a line of three hanging sacks branded with wombs (Silence me not – me ah rise!). Branded black on one side, they glisten with printed gold on the other. The branding has left parts of the hessian ruptured with holes, another process that helps to aestheticize an evocative display, rich in double meanings. Cowrie shells are replete with symbolic resonances as a substitute for money in parts of Africa, as jewellery when threaded into bracelets and necklaces, and as charms and symbols of the feminine. Cowries were a key currency in eighteenth and nineteenth Century trade for both enslaved peoples and gold, an historical elision that is nicely referenced in McLean’s work. 14 Issues of social, economic and gendered value haunt her installation, quietly suffusing its aesthetic power.

Silence me not…me ah rise, 2020, (detail), cowrie shells, 18 and 22 carat gold plated beads, gold waxed thread. Courtesy the artist.

11 See p. 5 below and footnote 13.

12 Camp, 2004, p.67

13 This form of resistance is explored in much of the recent scholarship on bondwomen. See, for example, Camp, 2004 and Jensen, 2006.

14 By the 18th century the cowrie had become the currency of choice along the trade routes of West Africa. It continued as a means of payment, also adopted by colonisers, until the early twentieth century. See M. Şaul (2004). Money in Colonial Transition: Cowries and Francs in West Africa. American Anthropologist, 106(1), 71-84.

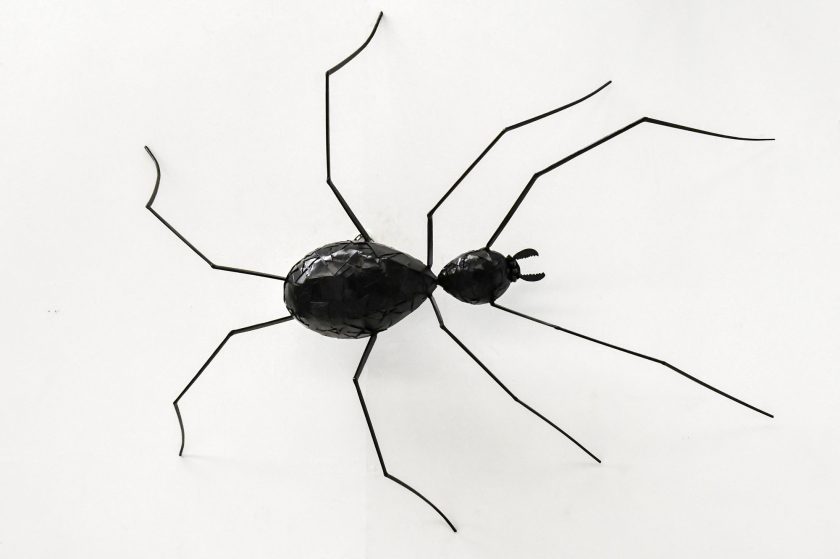

In the post-colonial Caribbean, Anansi is often celebrated as an historic symbol of individualism and slave resistance, a mythical figure that had enabled enslaved Africans to establish a sense of continuity with their African past.12

An oversized black metal spider (Anansi) appears to scale one of the exhibition walls. Smaller spiders also meander across the large wall hanging. These mischievous arachnids reference the cultural symbolism of Anansi, a character from Akan folklore. In West African, African American and Caribbean folklore Anansi often takes the form of a spider and is an inventive trickster, or god of knowledge of stories. In the post-colonial Caribbean, Anansi is often celebrated as an historic symbol of individualism and resistance, a mythical figure that had enabled enslaved Africans to establish a sense of continuity with their African past.15 As they scuttle across the hessian these emblems of black resistance remind the viewer of an oral history heavy in tales of loss and struggle. For an audience schooled in European art history, they may also evoke the French-American artist Louise Bourgeois’s series of huge metal spiders titled Maman (first cast in 1996), oversized symbols of maternal power and protection.

McLean’s multi-layered installation is replete with references that reaffirm the (often hidden) role of women in the history of Caribbean slavery. A row of twelve smaller sacks with laser-cut lettering on each that spells out ‘Ar’n’t I a Woman!’, is displayed along the right-hand entrance wall. They were stitched together by McLean and embroidered by a local women’s collective, Walsall Black Sisters, many of whom are from Jamaican Windrush families. McLean deploys women’s labour in the present post-imperial context to celebrate the struggles and achievements of their Caribbean ancestors in a colonial past. The central motif of the sturdy hessian sack, reduced here in scale, evokes not only the plantation container for sugar or coffee, but also poignant histories of infanticide, abortion and miscarriage – all too common in enslaved societies.16 Tiny bodies were often buried or hidden in sacks, a powerful signifier of women’s control – or lack of control – over their reproductive functions and economic ‘value’. And each sack is made with a threaded loop at the top, tied closed, like a lynching noose.

Repetition, or partial repetition, is another visual strategy deployed by McLean. What Briony Fer has described as a ‘serial aesthetic’17 has been imaginatively adopted not simply to reinforce and heighten the semiotic power of the material image (sack, cowrie shell, uterus, etc) but also to reveal an aesthetic power, a serial patterning that adds to the affective potential of the work. As in works by Bourgeois or American artist Eva Hesse, the intense, tactile nature of the materials, and their corporeal resonances, contribute to the effect – and affect – of repetition. McLean, however, rejects the ‘modern’ materials of latex or rubber often favoured by Bourgeois or Hesse (see, for example, Hesse’s Contingent, using textiles that more directly reference her colonised subjects. In Silence me not – me ah rise! she again uses materials heavy with historical significance, giving each a bondwoman’s name. In the process McLean liberates seriality from its minimalist associations and formulates her own ‘decolonised’ practice as a Trinidadian born artist working in a hybrid European context.18 The line of three hanging strips of hessian, suspended by threaded cowrie shells and gold beads, and imprinted with wombs echo the serial strategies of Hesse, while also reinforcing the complex, labour intensive nature of the former’s practice. Each hanging sack is bordered by brass strips at the top and bottom. McLean herself milled the brass strips in a metal workshop. Each has twenty holes for the strings of shells and beads suspended from the ceiling and below the hessian. The tiny beads are plated in a mixture of 18 and 22 carat gold. Such delicate, value-laden materials help to embellish a female subject previously seen largely as a vessel for economic profit within a colonial market-place. The artist originally planned to thread only dazzling 22 carat gold beads, but the outbreak of coronavirus during the production process caused sourcing problems. The impact of the coronavirus on the plans and schedules for this exhibition remind us that the modern globalised world can have both positive and negative effects on attempts to retrieve and rewrite some of its most painful histories.

The exhibition Ar’n’t I am Woman! presents works that are both visually seductive and heavy in emblematic references. The multi-toned hessian surfaces, tinkling cowrie shells, decorative branded wombs, gold embellishments and named figures, both reveal – and conceal – the work of the human hand. These are intensely handmade exhibits that both allure and challenge the viewer. Weaving, stitching, dyeing, screen printing and milling are the laborious processes that enable this installation to reconfigure and ventriloquise past activities adopted by bondwomen. They also contribute to a multi-layered visual celebration of those intensely physical practices of resistance and survival that have characterised the history of slavery. While the enslaved women referenced in Whitehead’s quote above was ‘branded, not for the first or the last time’ as she was fettered to her master, McLean’s sacks are imaginatively reconceived and re-branded as part of an aestheticized resistance to the ‘fettering’ and cruel exploitations of that history.

Gill Perry

January 2022

15 For example, ‘Anansi stories’ are Jamaican folk tales that were brought to Jamaica by Ashanti slaves and handed down through generations. For an excellent account of the roles and history of Anansi stories and folklore see Emily Zobel Marshall, Anansi’s Journey: A Story of Jamaican Cultural Resistance, (University of the West Indies Press, 2012).

16 See Jennifer L. Morgan, Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004)

17 Briony Fer, The Infinite Line: Re-Making Art After Modernism (London and Newhaven: Yale University Press, 2004).

18 For a useful overview of recent debates on the need for a ‘decolonising’ of Art History, see Catherine Grant and Dorothy Price, ‘Decolonising Art History’ in Art History, 43/1/February, 2020, pp. 8 – 66.

Karen McLean and The New Art Gallery Walsall would like to thank;

Samera Abid; Hannah Anderson; Arts Council England; Block 336; Simon Bloor; Tom Bloor; Vanley Burke; Kaia Charles; Elizabeth Hawley; Jane Hayes-Greenwood; Josephine Hengstewerth; Georgia Hewitt; Jeremy Hunt; International Curators Forum; Alex Jolly; Sophie Kelly; Indra Khanna; Damani Lewis; Peter Lewis; Hew Locke; Frederick McGrail; Gill Perry; Richard Rawlins; Deborah Robinson; Jon Sharples; Larissa Shaw; Stephen Snoddy; STEAMhouse; Stereographic; Kevin Storrar; Jessica Taylor; Anita Veigh; Walsall Black Sisters Collective; Emily Zobel Marshall.

Karen McLean

Birmingham-based artist Karen McLean grew up in Trinidad. Her artistic practice continues to be informed by the history, culture and folklore of the Caribbean and its inter-connections with the UK.

Solo exhibitions include Blue Power/A’r’n’t I a Woman! at Block 336, London (2021), Blue Power at Ort Gallery, Birmingham (2018), The Precariat at Lewisham Art House, London (2017), three at BPN Architects, Birmingham (2014) and Trove at Edible Eastside, Birmingham (2012). Group exhibitions include MOTHERSHIP at The Sawmills, London (2016), Goldsmiths MFA show (2015), Independence Exhibition at Hackney Museum, London (2012), Trinidad & Tobago Film Festival at Medulla Art Gallery, Trinidad (2012), Trinidad & Tobago Cultural Village (2012), British Summertime 2 at The New Art Gallery Walsall and mac, Birmingham (2011) and Folkestone Triennial Fringe (2011).

Her work has recently featured in Benedita Menezes’ essay, If Eve ain’t in your Garden: Intersections between Lil Nas X, Karen McLean and Bronzino in Umbigo, #79, Lisbon, Portugal and is also discussed in Gill Perry’s book Playing at Home: The House in Contemporary Art, Reaktion Books Ltd, 2013.

Karen was recently a selector for the Gallery of Living History’s Schools Competition.

Her work has been acquired by the Soho Arts Collection.

Karen was awarded an MA in Fine Art at Goldsmiths, University of London in 2015 and BA (Hons) (First Class) at Birmingham City University in 2009.

Gill Perry

Gill Perry is Emeritus Professor of Art History at the Open University. She has published widely on eighteenth century and modern and contemporary art with a special interest in women’s practice and gender relations, and (more recently) ‘global’ art histories in the UK, Ireland, Europe and beyond. Her books include:

Paula Modersohn Becker: Her Life and Work, The Women’s Press, 1979, Women Artists and the Parisian Avant-Garde: Modernism and ‘Feminine’ Art 1900 to the late 1920s, MUP, 1995; Gender and Art (ed. and co-author), Yale UP, 1999; Difference and Excess in Contemporary Art: The Visibility of Women’s Practice, (ed.) Blackwells, 2003; Themes in Contemporary Art, (ed.) Yale UP, 2004; Spectacular Flirtations: Viewing the Actress in British Art 1768-1820, Yale UP, 2007; The First Actresses: Nell Gwynn to Sarah Siddons, National Portrait Gallery London, 2011-2012. Relationships between gender and ‘home’ feature in her book Playing at Home: The House in Contemporary Art, Reaktion, 2013 and catalogue essay for the exhibition Women House, Paris and Washington, 2017-18. Her forthcoming book is titled Islands in Contemporary Art (Reaktion, 2022), and features Karen’s work.

Block 336 showed Karen’s work in July 2021 and generated a rich range of resources which can be found here.

All images © Karen McLean unless otherwise stated. Text © Gill Perry.