Where Are All the British Asian Artists?

by Alice Correia

In late 2015, a magazine headline asked: “where are all the British Asian artists?” The question preceded an article about the Birmingham born, Glasgow-based British-Sikh artist Hardeep Pandhal. While The World That Belongs to Us positions Pandhal within a globally dispersed network of South Asian diaspora artists, in 2015 the journalist Alun Evans attempted to situate and contextualise Pandhal and his work within a history of British-Asian art. Evans identified Anish Kapoor, Zarina Bhimji, Shezad Dawood, Haroon Mirza, and Chila Kumari Burman as British-Asian success stories, while simultaneously concluding, “if you’re not a dedicated follower, practitioner or scholar of British contemporary art, you’d be forgiven for never having heard of them before”.1

While the headline may have been clickbait, it nonetheless raised a number of interconnected questions that went beyond an ability (or not) to name a handful of artists. Because, once you start looking, there have been, and continue to be, many artists of South Asian heritage working in Britain, even though their contributions to British art have not been adequately recorded, exhibited, or published. It is notable that to date, there is only one book dedicated to the history of South Asian diaspora artists in Britain.2 The widespread cultural amnesia about artists as diverse as Amal Ghosh, Anita Kaushik, and Juginder Lamba, allows for a situation in which the apparent scarcity of British-Asian artists can become the headline.

Given that archives such as the Panchayat Collection tell rich and expansive stories of British-Asian art,3 how do we account for absence of those stories from mainstream art history? Working in London during the 1950s, artists including FN Souza, Anwar Jalal Shemza and Avinash Chandra found that their work was excluded from narratives of modern painting as critics and curators expected to see discernible exotic references in their work.4 In 1981, reflecting on the nature of Britain’s white art world, artist Balraj Khanna wrote:

Hypocrisy, superciliousness, vanity and arrogance are some of its traits, mainly located in the cliques that control art journalism, exposure, sponsorship and general patronage. Arguably it is tough for any artist at the best of times, but for some reason it is tougher even for artists as good, say, as Avinash Chandra, Francis Souza and Rasheed Araeen; the lesser ones do not stand a chance. Some may say this is a kind of racial discrimination and they won’t be wrong if they do.5

So how do we challenge such long-standing, structural, institutionalised racism and neglect by Britain’s art historians, curators, and galleries?

1 Alun Evans, “Where Are All the British Asian Artists?” Vice Magazine, 23 September 2015, https://www.vice.com/en/article/exq5yw/where-are-all-the-british-asian-artists-623, accessed 19 October 2023.

2 Amal Ghosh and Juginder Lamba (eds.), Beyond Frontiers: Contemporary British Art by Artists of South Asian Descent, London: Saffron Press, 2001. However, it’s important to note that a new generation of art historians including Alina Khakoo and Hassan Vawda are undertaking and publishing research on British South Asian diaspora artists.

3 See Panchayat Collection, Tate Library and Archive, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/panchayat-collection-research-resource, accessed 19 October 2023.

4 See Alice Correia, “‘Respectable Exotics’: Exhibiting South Asian Modernists in Britain, 1958 and 2017”, Visual Culture in Britain, vol.23, no.3 January 2021, doi.org/10.1080/14714787.2020.1852887

5 Balraj Khanna, “Obscure but Important”, Art Monthly, no.36, October 1980, p.25.

In the introduction to his groundbreaking study, The Location of Culture, Homi Bhabha asserted that “The Western metropole must confront its postcolonial history, told by its influx of post-war migrants and refugees, as an indigenous or native narrative internal to its national identity”.6 Following Bhabha, if we are to move forward as a coherent and cohesive multicultural society we must pay attention to Britian’s global connections, and fully recognise diaspora artistic practice as internal to narratives of British art. This means attending to the histories of Asian, black and diaspora artists, their exhibitions, and the debates that took place around their work; it means recording and analysing the texts that were written and the pamphlets that were published. And it means excavating archives for stories of art that occurred outside of the dominant metropolitan centre. The dominant story of British art in the twentieth century has been London-centric: the Bloomsbury group; Swinging London and 1960s Pop; Goldsmiths College and the yBas. But outside of the capital, towns and cities including Walsall, Sheffield, Bradford, and Rochdale have been sites of innovative, and culturally diverse, artistic ecosystems. Attempting to redress the art historical neglect faced by South Asian diaspora artists in Britain is then to also challenge the pejorative dismissal and exclusion of artistic practice from the regions.

What we find when we move away from the metropolitan centre and move into the margins are rich histories of creativity. Since the 1960s, public collections and galleries across the Midlands and Northern England, staffed with socio-politically engaged curators, have been acquiring work by, and staging significant exhibitions of, South Asian diaspora artists. Leicestershire County Council Artworks Collection holds important works by Avinash Chandra and Tyeb Mehta, acquired in the 1960s, as part of its strategy to build a nationally significant collection of modern art. During the 1970s, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, acquired works by Balraj Khanna and Anwar Jalal Shemza, and in the 1980s and early 1990s, under the guidance of Nima Poovaya-Smith (Keeper of Arts), assembled an unparalleled collection of contemporary art by South Asian diaspora artists.7 More recently, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery became home to the South Asian Diaspora Arts Archive (SADAA). However, within a national context such engagement with South Asian diaspora artists was, and remains unusual. Despite the efforts of artist, curator, and critic Rasheed Araeen to champion the likes of Chandra, Khanna, Shemza and Souza in his groundbreaking exhibition, The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain, in 1989, they were, until very recently, largely excluded from exhibitions and publications on twentieth century British art.8

“The Western metropole must confront its postcolonial history, told by its influx of post-war migrants and refugees, as an indigenous or native narrative internal to its national identity”

The Location of Culture, Homi Bhabha

Throughout the 1980s, Rasheed Araeen was at the forefront of debates about the representation of black and Asian artists in British art galleries and collections. During this period, groups of Midlands-based artists collaborated to stage exhibitions and public debates about the place and representation of artists of colour within structurally racist institutions. Araeen was a speaker at the First National Convention of Black Art, staged at Wolverhampton Polytechnic in October 1982, organised by the BLK Art Group, whose members included Eddie Chambers, Keith Piper, Donald Rodney and Marlene Smith.9 At this time in the UK, Black was broadly understood as a politically strategic term denoting anti-racist solidarity amongst people of colour and diasporic people. As cultural theorist Stuart Hall reflected, the term Black, “came to provide the organizing category of a new politics of resistance, amongst groups and communities with, in fact, very different histories, traditions and ethnic identities”.10 In response to demands from black and Asian artists that their work be exhibited, by the mid-1980s, group exhibitions of Black art and Asian art were periodically staged in galleries from Liverpool and Oldham, to Bristol and London. However, these exhibitions were often sprawling events in which participating artists and their work had little in common beyond their non-whiteness.11 While these exhibitions were useful for facilitating the rare display of work by artists of colour, in 1986 Eddie Chambers raised a note of caution. In an article titled, The Marginalisation of Black Art, Chambers argued that in general, the patronage offered to artists of colour by white-led institutions was exploitative: Asian and black contemporary artists found themselves segregated from their white peers, while critical engagement with the form and materials of their work remained negligible.12

6 Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture, London: Routledge, 1993, p.6.

7 See Nima Poovaya-Smith, “Keys to the magic kingdom: The new transcultural collections of Bradford Art Galleries and Museums”, in Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn (eds.), Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum, London: Routledge, 1998, pp.111-125, p.115.

8 Rasheed Araeen (ed.), The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain, exhibition catalogue, London: Southbank Centre, 1989. The exhibition, Post-War Modern: New Art in Britain, 1945-1965, staged at the Barbican, London, 2022, and its attendant catalogue, did much to redress the pervasive exclusion of artist of colour from narratives of post-war British art.

9 See BLK Art Group Research Project, http://blkartgroup.info

10 Stuart Hall, “New Ethnicities (1988)”, in James Procter (ed.), Writing black Britain 1948-1998: An interdisciplinary anthology, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000, pp.265-275, p.266.

11 These criticisms were particularly levelled at the exhibition, From Two Worlds, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1986. See Eddie Chambers, “Mainstream Capers”, ArtRage, no.14, Autumn 1986, pp.31, 33–4.

12 Eddie Chambers, “The Marginalisation of Black Art”, Race Today Review, February 1986, pp.32–3. Reproduced in Alice Correia (ed.), What is Black Art? Writings on African, Caribbean and Asian Artists in Britain, 1981-1989, London: Penguin, 2022, pp.75-80.

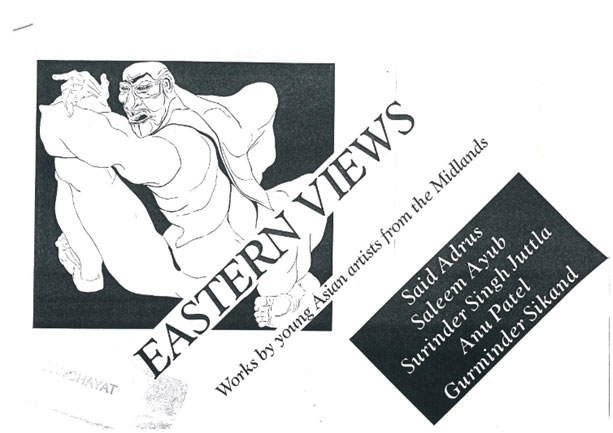

Eastern Views: Works by Young Asian Artists from the Midlands, Leicestershire Museum Services, 1985.

Indeed, discussing the work and career of painter Gurminder Sikand, Tim Youngs recorded that although as “a member of Nottingham Asian Artists’ Group, together with Sardul Gill and Said Adrus, she has benefited from the funding (by East Midlands Arts)”, Sikand nonetheless “argues that pressures can be exerted which tend to promote stereotypes at the expense of individual expression”.13 The type of negative stereotyping that Sikand observed can be levelled at exhibitions such as Eastern Views: Works by Young Asian Artists from the Midlands, which included work by Said Adrus, Saleem Ayub, Surinder Singh Juttla, Anu Patel and Sikand, at New Walk Museum, Leicester. While well-intentioned, read with hindsight, the exhibition’s title and accompanying press release repeat exoticizing and othering tropes found in colonial-era interpretations of Indian art. Aware of these debates surrounding the representation of black and South Asian artists in British galleries, by the later 1980s curator Deborah Robinson, with the support of the Director Peter Jenkinson, sought to embed equality, diversity and social-consciousness within the exhibition programme at Walsall Museum and Art Gallery in ways that went beyond tokenistic gestures.

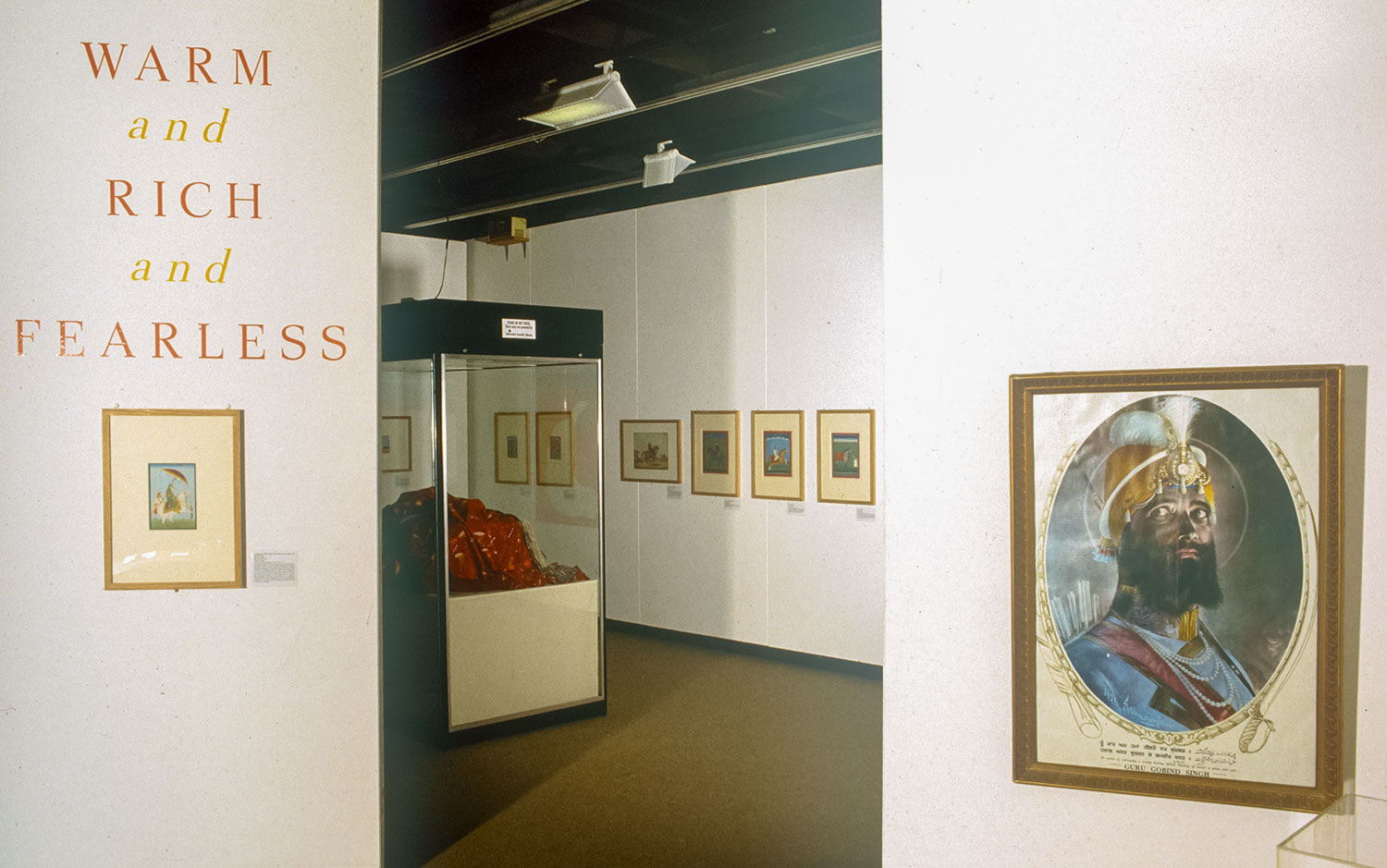

Warm and Rich and Fearless, Walsall Museum and Art Gallery, Spring 1992. Digitised slides from Walsall’s archives.

Staff at Walsall Museum and Art Gallery were conscious that by the mid-1990s, approximately 7 per-cent of the borough’s population was of Asian origin, and that 7 out of 10 visitors to the gallery came from the local area.14 As such, the gallery undertook a curatorial decision to stage exhibitions that were locally relevant. Curators sought to develop an exhibition programme that included displays by South Asian diaspora artists, and those that addressed South Asian religious and cultural identities. One such exhibition was Warm and Rich and Fearless (Spring 1992), an exhibition of Sikh art that had been organised by Cartwright Hall.15 The exhibition sought to give insight into Sikh history and culture, and included sacred texts, paintings, costumes, textiles, and weaponry; many of the artworks were lent by the V&A museum and the Royal Collection and had not been previously exhibited. When the exhibition toured to Walsall, care was taken to adjust the displays for local audiences, and arts-teacher Amarjit Singh was employed as the exhibition’s Community Events co-ordinator. In this role, Singh worked with two Gurudwaras and members of the Sikh community to collaboratively programme a series of musical performances, discussions, story-telling sessions, and art workshops led by textile artist Sarbjit Natt. While the exhibition attracted new audiences and forged new networks and collaborations, in their evaluation of the project Singh and Walsall Education Officer Alison Cox nonetheless recognised that this was a one-off project, supported by external funds. The question of how to embed diversity within the fabric of the gallery and its programme remained; they rightly asked: “How can museums dominated by culturally unrepresentative art and history collections begin to represent diversity without appearing tokenistic?”16

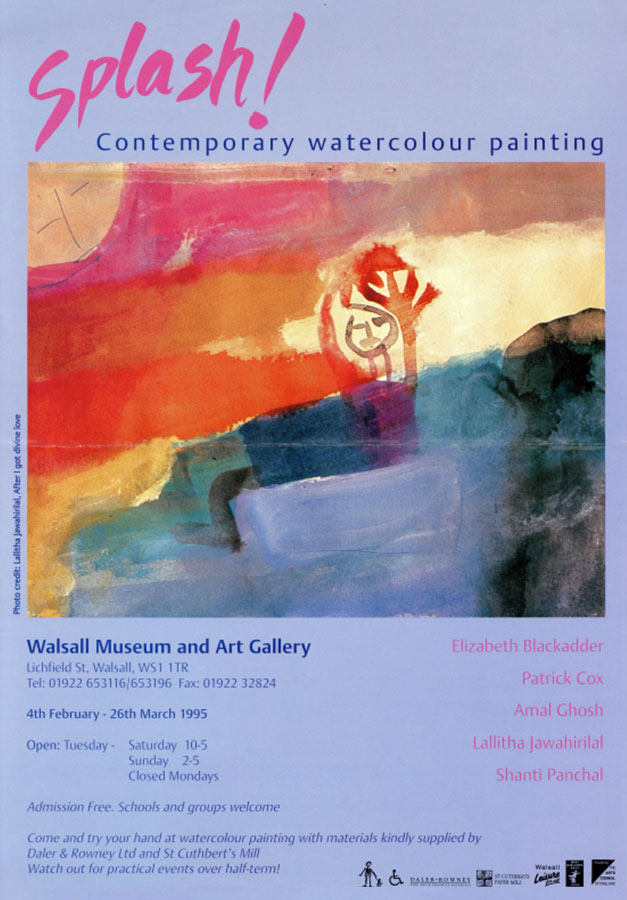

One strategy that curators at Walsall adopted was to ensure that hitherto marginalised artists were actively included within its programme of contemporary art exhibitions. Offering artists solo shows and taking care that group exhibitions included artists from a range of diverse backgrounds, during the 1990s Walsall took steps towards establishing an inclusive exhibition programme. Group exhibitions such as Confrontations (1993) and Splash! Contemporary Watercolour Painting (1995) are important because they positioned South Asian diaspora artists alongside their white peers according to a thematic subject matter or the material form of their work.

6 Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture, London: Routledge, 1993, p.6.

7 See Nima Poovaya-Smith, “Keys to the magic kingdom: The new transcultural collections of Bradford Art Galleries and Museums”, in Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn (eds.), Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum, London: Routledge, 1998, pp.111-125, p.115.

8 Rasheed Araeen (ed.), The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain, exhibition catalogue, London: Southbank Centre, 1989. The exhibition, Post-War Modern: New Art in Britain, 1945-1965, staged at the Barbican, London, 2022, and its attendant catalogue, did much to redress the pervasive exclusion of artist of colour from narratives of post-war British art.

9 See BLK Art Group Research Project, http://blkartgroup.info

10 Stuart Hall, “New Ethnicities (1988)”, in James Procter (ed.), Writing black Britain 1948-1998: An interdisciplinary anthology, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000, pp.265-275, p.266.

11 These criticisms were particularly levelled at the exhibition, From Two Worlds, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1986. See Eddie Chambers, “Mainstream Capers”, ArtRage, no.14, Autumn 1986, pp.31, 33–4.

12 Eddie Chambers, “The Marginalisation of Black Art”, Race Today Review, February 1986, pp.32–3. Reproduced in Alice Correia (ed.), What is Black Art? Writings on African, Caribbean and Asian Artists in Britain, 1981-1989, London: Penguin, 2022, pp.75-80.

Confrontations, Walsall Museum and Art Gallery, 1993. Digitised slides from Walsall’s archives.

Confrontations brought together the work of eight contemporary artists, each with different cultural backgrounds and life experiences, in order to challenge stereotypes, rectify misrepresentations, and confront preconceived prejudices and biases. Works by Chila Kumari Burman, Claire Collison, Mary Duffy, Roshini Kempadoo, Shaheen Merali, Elizabeth Rowe, Lesley Sanderson and Nina Saunders, addressed trans- and gender discrimination; disability rights; the exoticisation of racialised bodies and Euro-centric perceptions of the world. Including the works by Burman and Kempadoo that were exhibited in Confrontations, which are now held in the Walsall collection, The World that Belongs to Us echoes and reexamines the ways that the 1993 exhibition challenged normative histories and gave space to often maligned and marginalised voices. The artists included in Confrontations were able to address the complexities of their identities, while audiences were encouraged to find affinities between themselves and the very different subject positions on display. For Jacques Rangasamy, “The artist’s grievances have unique and individual resonances, but their visual enunciation in the work displays an openness to affinities: those who find in them an echo of their own experience might derive support and inspiration as well”.17 In its attempt to break down divisions between us and them, Confrontations seems, in retrospect, to build on Stuart Hall’s call to challenge “binary systems of representation” and the constructed boundaries that delineate “belongingness and otherness”.18

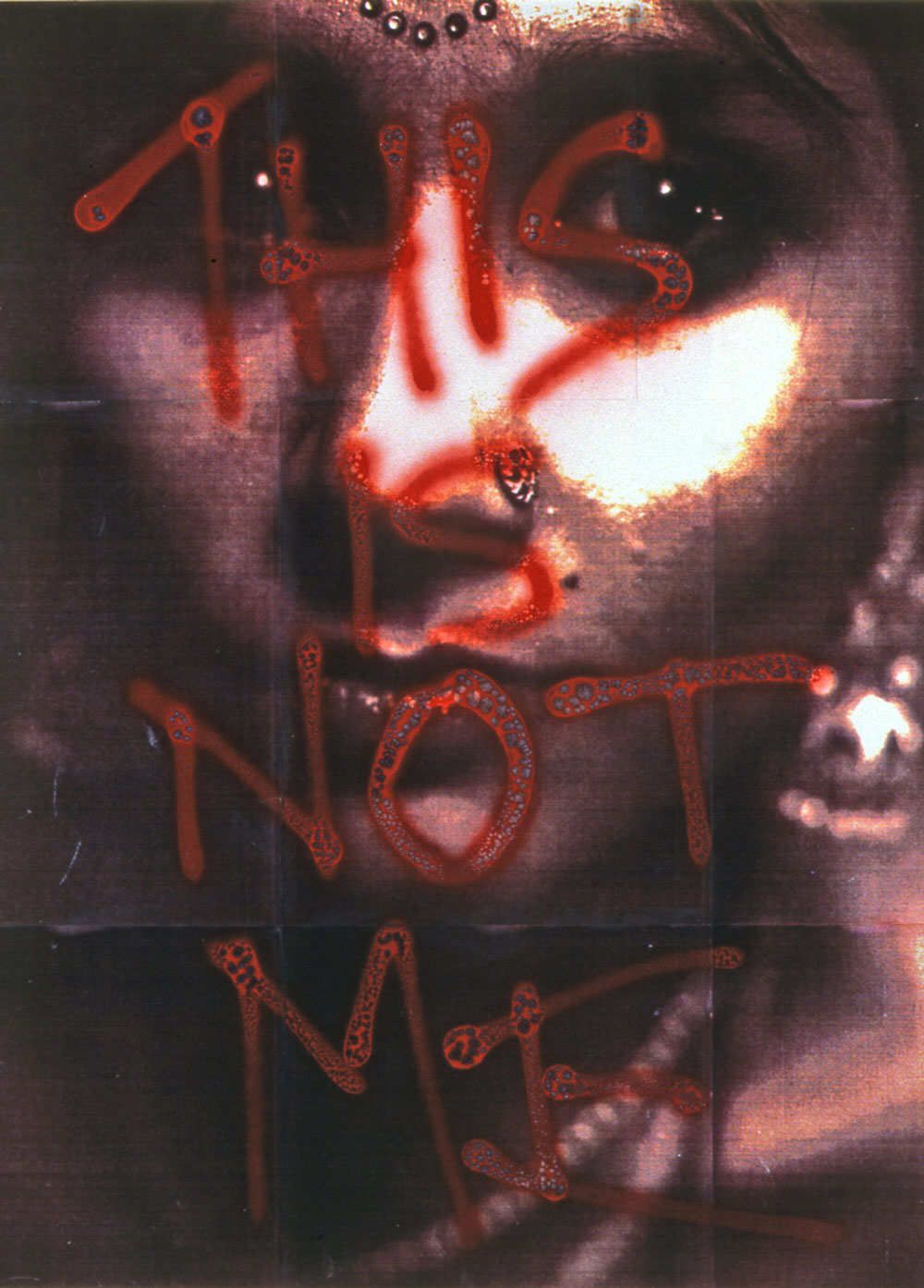

LEFT: Chila Kumari Singh Burman, Body Weapons (This is not Me), 1992, digital images on paper. The New Art Gallery Walsall Permanent Collection. © Chila Kumari Singh Burman. All rights reserved, DACS, 2023. RIGHT: Roshini Kempadoo, Changing Spaces, (detail), 1993, digital images on board. The New Art Gallery Walsall Permanent Collection. © Roshini Kempadoo.

Although each artist included in Confrontations addressed a different stereotype or prejudice in their work, cumulatively, the participation of Chila Kumari Burman, Roshini Kempadoo and Shaheen Merali also confronted expectations about British-Asian identities. Historically, British society has tended to homogenise South Asian communities; indeed, the term South Asian is short-hand for a large number of people, spread across the globe with different national allegiances, social classes, religions and castes.19 Born in Liverpool, Burman has described herself as Punjabi-Scouse; Kempadoo is Indo-Guyanese; while Merali was born in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, of Gujarati heritage. The identities of these three artists cross multiple continents. In their work they explore the global interconnections of living in the diaspora, and challenge Eurocentric heteronormative social hierarchies that would keep others in their place. Just as Hall proposed identity as a set of negotiations that adapts to the circumstances of global dispersal and settlement, Burman’s self-portraits (above left) and Kempadoo’s photomontages (above right) demonstrate how “Diaspora identities are those which are constantly producing and reproducing themselves anew, through transformation and difference”.20

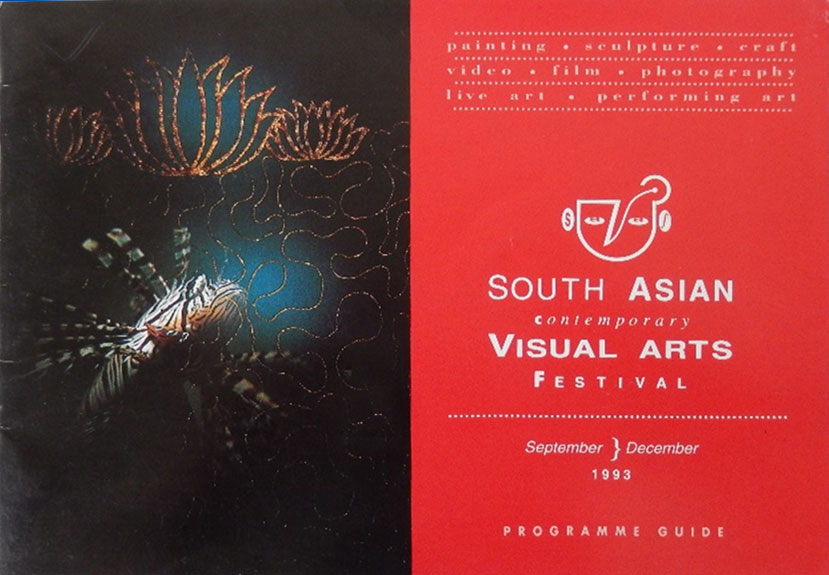

South Asian Contemporary Visual Arts Festival, 1993, festival programme showing detail of Keith Khan and Ali Mehdi Zaidi, Captives, Walsall Museum and Art Gallery on front cover.

Celebrating this diversity of South Asian diaspora identities, between September and December 1993, sculptor Juginder Lamba curated the South Asian Contemporary Visual Arts Festival. The festival exhibited over 50 artists of South Asian descent in 18 venues across the West Midlands, including Birmingham, Coventry, Sandwell, Shropshire, Stafford, Stoke, Walsall, Warwick, Wolverhampton, Worcester. 21 However, although celebratory, Lamba explained that the Festival was organised in response to the perceived “lack of any significant visual art provision for the large Asian community in the West Midlands and the conspicuous under-representation of the work of artists of South Asian origin in the region’s major venues”.22 The festival profiled the work of British-based artists, working in a range of media, including painting, sculpture, ceramics, textiles, and performance, and whose work addressed both formal concerns and social politics. While Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery staged the large-scale group exhibition, Transition of Riches (Sept-Nov 1993), which showcased the work of eight artists, Walsall Museum and Art Gallery staged the ambitious and daring installation, Captives (September-October 1993).

13 Tim Youngs, “Gurminder Sikand at Mansfield Community Arts Centre”, Stepping Out, February 1986, p.11.

14 See Alison Cox with Amarjit Singh, “Walsall Museum and Art Gallery and the Sikh Community: a case study”, in Eilean Hooper-Greenhill (ed.), Cultural Diversity: Developing Museum Audiences in Britian, London: Leicester University Press/ Cassell, 1997, pp.159-167, p.159.

15 For discussion of the curatorial development of Warm and Rich and Fearless at Cartwright Hall, see Nima Poovaya-Smith, “Academic and Public domains: When is a dagger a sword?”, in Eilean Hooper-Greenhill (ed.), Cultural Diversity: Developing Museum Audiences in Britian, London: Leicester University Press/ Cassell, 1997, pp.149-158.

16 Cox with Singh, 1997, p.167.

17 Jacques Rangasamy, “Confrontations”, Third Text, vol.7, no.22, 1993, pp.99-106, p.99.

18 Hall, 1988, p.269.

19 See Avtar Brah, Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities, London: Routledge, 1996, pp.67–83.

20 Stuart Hall, “Cultural Identity and Diaspora”, in Jonathan Rutherford (ed.), Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1990, pp.222-237, p.235.

21 Juginder Lamba, South Asian Contemporary Visual Arts Festival: Final Report, July 1994.

22 Lamba, 1994, p.1.

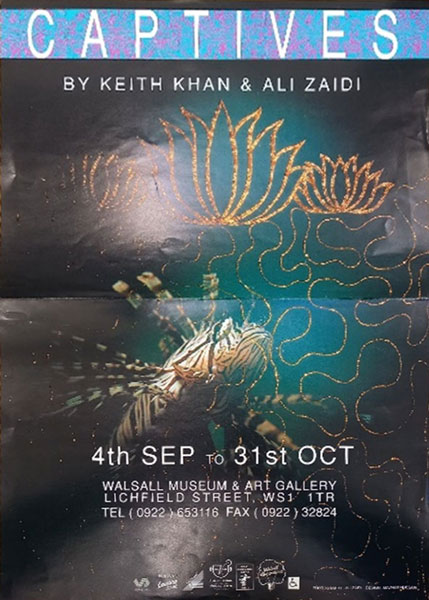

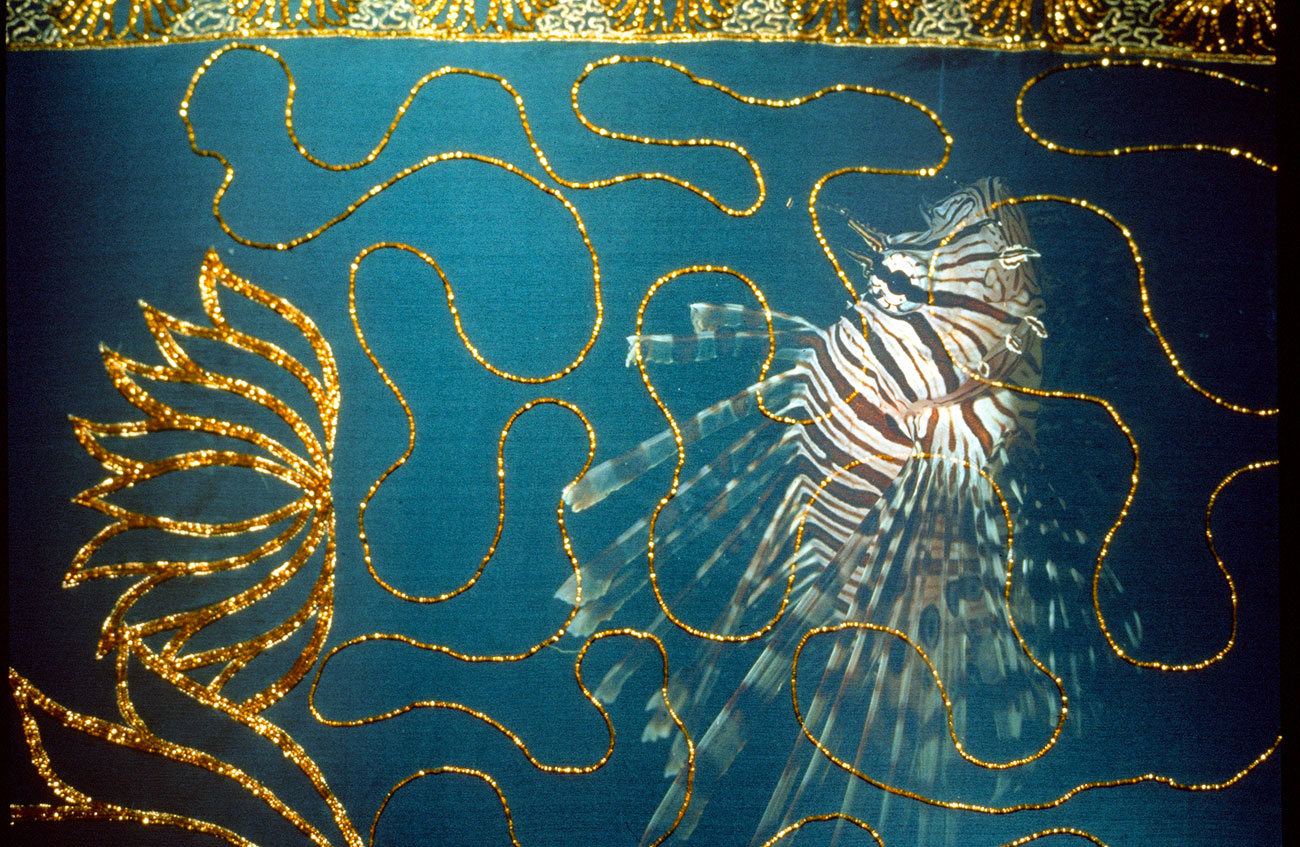

LEFT: Keith Khan and Ali Mehdi Zaidi, Captives, Walsall Museum and Art Gallery, exhibition poster | RIGHT: Captives, Installation view. Digitised slides from Walsall’s archives.

Captives was a collaboration between Keith Khan and Ali Mehdi Zaidi, in which live tropical fish from different continents were exhibited in custom-made tanks within the gallery. The fish were accompanied by wood carvings and textiles from Pakistan, and calligraphy and photography. Placed in different tanks, the captive fish were “segregated according to their geographical origins”,23 and alongside the other artworks and objects, audiences were invited to consider how global cultures are catalogued and displayed in Britain according to colonial systems of classification. It is important to note that eighteenth and nineteenth century scientific systems for classifying and cataloguing the natural world were developed in tandem with colonial systems of exploitation and extraction.24 Celebrated botanists such as Carl Linnaeus – who developed classificatory schemes for people as well as plants – are today regarded as “agents of empire”.25 The presence of the live fish in the gallery refuted the notion that foreign, exotic, specimens are static and unchanging. During the exhibition, artists Nina Edge and Bhajan Hunjan assisted visitors in creating contributions to the installation, reinforcing the point that art, culture, and indeed, life, is in a constant state of transformation.

Captives, Installation view (detail) Walsall Museum and Art Gallery, 1993. Digitised slides from Walsall’s archives.

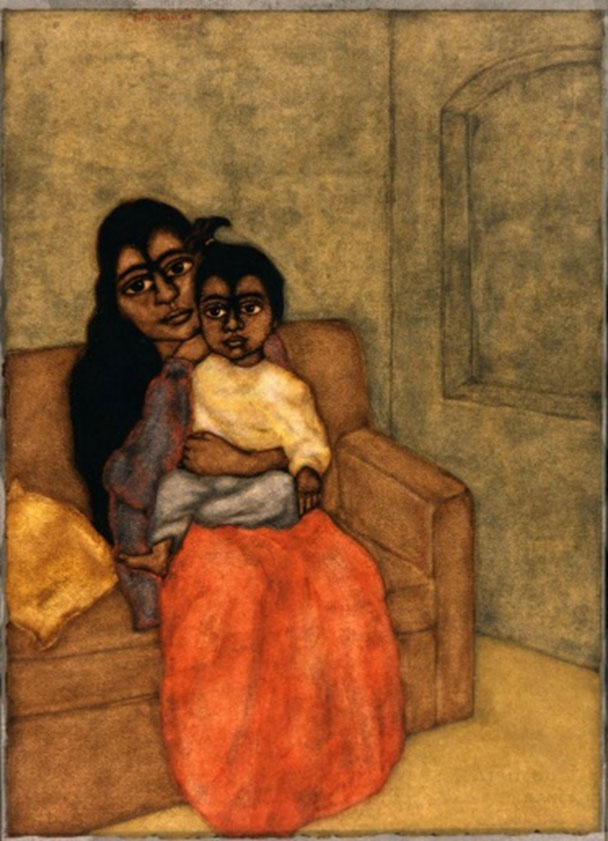

LEFT: Splash! Contemporary Watercolour Painting, 1995, exhibition poster. RIGHT: Shanti Panchal, Mother and Baby, 1991. The New Art Gallery Walsall Permanent Collection. © Shanti Panchal.

In her landmark essay, The Work Between Us, of 1997, the artist and critic Jean Fisher observed that during the 1990s diaspora art had become entangled with identity politics, often to its detriment. She noted that “art is currently ensnared in debates of cultural difference and identity that are noticeably lacking in critical discussion about the work itself”.26 Arguably, Splash! Contemporary Watercolour Painting staged at Walsall Museum and Art Gallery in 1985 was one of a handful of exhibitions during the 1990s that actively sought to prioritise the work of art on its own terms. Exhibiting three South Asian diaspora artists, Amal Ghosh, Lallitha Jawahirilal and Shanti Panchal, alongside the Scottish painter Elizabeth Blackadder, and West-Midlands based artist Patrick Cox, Splash! sought to challenge dismissive expectations of watercolour painting as “pretty flowers and pretty landscapes”.27 The exhibition explored the different ways that each artist utilised watercolour paint and the specific properties of the medium. In so doing, the exhibition reorientated interpretations of work by Ghosh, Jawahirilal and Panchal away from identity politics, and towards each of the artist’s painterly processes.

Lallitha Jawahirilal, After I got Divine Love and Steadied Down, 1991. The New Art Gallery Walsall Permanent Collection. © Lallitha Jawahirilal.

At first glance, it would appear that the paintings by Panchal and Jawahirilal exhibited in Splash!, and subsequently acquired for the Walsall collection, are very different. Panchal’s figurative painting is naturalistic, and precise. The titular mother and baby sit on a sofa and look to their right. The alert gaze of the baby suggests that something, or someone, out of frame has caught their attention. In comparison, Jawahirilal’s painting, After I got Divine Love and Steadied Down, 1991 comprises gestural ribbons of colour, through which a child-like stick-figure seems to be falling, or perhaps sliding.

Early in his career, Panchal developed a mode of working whereby “watercolour is not just painted onto the surface, but injected into the paper”,28 to achieve areas of saturated colour. While the focal point of his painting is the two figures, Mother and Baby, may also be regarded as a formal study in the arrangement of large masses of colour and empty space. Panchal’s composition seems to balance abstract elements with the figurative to convey nuanced sensibilities. Despite the differences in their handling of paint, Jawahirilal’s watercolour also explores the ability of colour to convey emotion and feeling, and the interplay between figurative and abstract elements. While Panchal’s dense saturated colour creates a sense of intensity, Jawahirilal has harnessed watercolour’s fluidity and opacity to create a work that has a lightness and dream-like quality.

Gurminder Sikand, Maidens, Trees and Deities at Walsall Museum and Art Gallery, installation view, 1995. Digitised slides from Walsall’s archives.

While Splash! was on display the main gallery space at Walsall, Gurminder Sikand’s solo exhibition of new paintings, Maidens, Trees and Deities was staged concurrently in the smaller gallery known as The Other Space. Sikand’s exhibition comprised watercolour and gouache paintings on paper, many of which depicted nude female figures seated or standing in semi-rural landscapes. Much of the critical writing about Sikand’s work during the 1990s sought to link her practice to the Mithila artists of Bihar, and nineteenth century Kalighat paintings.29 While these reference points were, by the artist’s admission important to her artistic development,30 the repeated prioritisation of South Asian visual traditions in writing about Sikand’s work left little scope for other routes of interpretation. For example, there has been relatively little discussion of Sikand’s depiction of women and trees as eco-feminist statements, despite her known interest in the non-violent protests of the women-led Chipko environmental movement in northern India.31

Where are all the British Asian artists? The generation of artists who emerged in the 1980s and 90s discussed here, and those included in The World that Belongs to Us, continue to work and exhibit; examples of their artworks are held (albeit in small quantities) in public, civic and national collections across the UK. So, I’d like to conclude with a different set of questions: Where is the writing about these artists? Who is undertaking the research? And how are their works exhibited and historicised today? This essay has given a brief overview of a handful of artists and a selection of exhibitions, but there is much more work to be done, and many more stories to tell. By placing South Asian diaspora art in Britain made during the 1980s and 90s in intergenerational and transnational dialogues emergent in the diasporic imaginaries of USA and Canada, The World that Belongs to Us is an important step in that journey.

Alice Correia

23 Anon. Captives, exhibition introduction/ poster, Walsall Museum and Art Gallery, 1993.

24 See Ros Gray and Shela Sheikh, “The Wretched Earth: Botanical Conflicts and Artistic Interventions Introduction”, Third Text, vol.32, nos.2-3, 2018, pp.163-175, p.165.

25 Londa Schiebinger, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007, p.11.

26 Jean Fisher, “The Work Between Us (1997)”, in Jean Fisher, Vampire in the Text, London: Iniva, pp.266-269, p.266.

27 Shanti Panchal, “Portrait of the artist”, The Artist’s and Illustrator’s Magazine, April 1990, p.20-23, p.20

28 Panchal, 1990, p.20

29 See for example, Fine Material for a Dream…?: A Reappraisal of Orientalism; 19th and 20th Century Fine Art and Popular Culture juxtaposed with paintings, video and photography by contemporary artists, exhibition catalogue, Preston: Harris Museum and Art Gallery, 1992, p.6.

30 See Gurminder Sikand, “The Patterns of Culture I Currently Wear”, in Ghosh and Lamba, 2001, pp.214-217.

31 It is hoped that Sikand’s inclusion in the exhibition Re/Sisters: A Lens on Gender and Ecology, Barbican Art Gallery, 5 October 2023-14 January 2024, with rectify this. See Alice Correia, “On Environmental Catastrophe and (Not) Exhibiting Black British Feminist Art”, Wasafiri, forthcoming Spring 2024.

Biography

Dr Alice Correia is a curator and art historian. She co-curated the major exhibition A Tall Order!: Rochdale Art Gallery in the 1980s at Touchstones, Rochdale Feb-May, 2023. Her edited anthology, What is Black Art? Writings on artists of African, Asian and Caribbean Heritage in Britain, 1981-1989, published by Penguin in 2022, and her essay, “Representing South Asian Women in Britain” is included in the exhibition catalogue for Women in Revolt at Tate Britain, Nov 2023- April 2024. She is Chair of Trustees of Third Text and co-Chair of the British Art Network’s Black British Art Research Group. She is currently a Research Fellow at the Decolonizing Arts Institute, University of the Arts, London.

Bibliography

Publications

Correia, A. (ed.) (2022) What is Black Art?. Penguin Books Ltd.

Aikens, N. and Robles, E. (eds.) (2019) The Place Is Here: The Work of Black Artists in 1980s Britain. Sternberg Press

Reckitt, H. (2018) The Art of Feminism: Images that Shaped the Fight for Equality. Tate Publishing

Articles & Essays:

Correia, A. (2020) Consistently Present: Alice Correia on South Asian Women Artists, Animating Archives.

Correia, A. (2020) ‘Picturing Resistance and Resilience: South Asian Identities in the Work of Chila Kumari Burman’, Visual Culture in Britain, 21(2), pp 199 – 226.

Correia, A. (2019) ‘Researching Exhibitions of South Asian Women Artists in Britain in the 1980s’, British Art Studies, Issue 13.

Correia, A. (2017) ‘Diasporic Returns: Reading Partition in Contemporary Art’, Third Text, 31(2-3), pp 321 – 340.