Karen McLean

Ar’n’t I a Woman!

The New Art Gallery Walsall

18 February – 3 July 2022

Karen McLean’s exhibition A’rn’t I a Woman! should have opened at The New Art Gallery Walsall on 1 May 2020. Sadly it was delayed due to the pandemic but Karen did get to show some of the work at Block 336 in Brixton, London in May/June 2020. We are delighted to finally be able to open the exhibition in Walsall, in the space the work was designed for.

This exhibition guide/microsite contains two specially commissioned essays by Gill Perry and Emily Zobel Marshall. It will be updated further with documentation of the exhibition in Walsall.

Following Anansi’s Web:

The Power of Caribbean Storytelling

by Emily Zobel Marshall

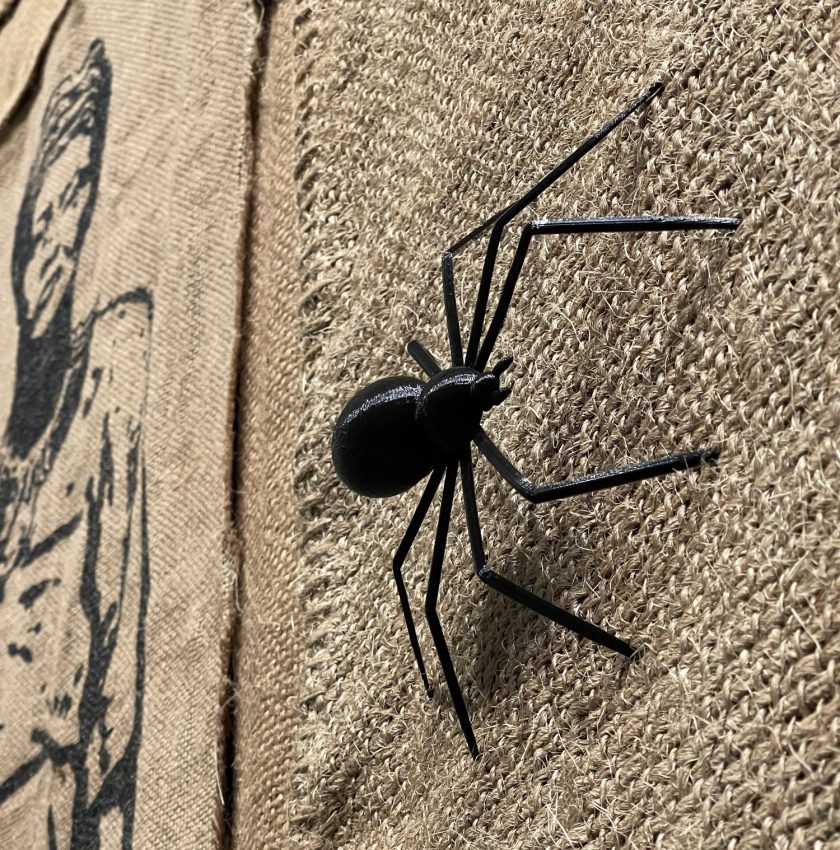

This piece has been commissioned to accompany the exhibition ‘Ar’n’t I a Woman!’ by artist Karen McLean. As you journey through the exhibition, notice the 3-D printed representations of Anansi the spider crawling across sackcloth and hiding on the walls. Anansi is a cunning creature who sees everything, but often remains hidden, which gives him an advantage over his adversaries. You might ask yourself, who is watching who?

The Power of Storytelling

What is the purpose of telling stories? In the west, storytelling is often associated with childhood. The west has, to some extent, lost touch with oral storytelling as a communal activity. Yet across the globe stories have played a vital role in shaping our sense of identity, society and nationality. Before the age of the television, storytelling brought young and old together. More importantly, stories have the capacity to help people survive and resist oppressive regimes.

For the past two decades I have been researching the folk tales of Anansi the spider. Anansi stories originated in West Africa and were brought by enslaved Africans to the Caribbean. Along with African American folk heroes like Brer Rabbit, trickster folktales told by enslaved people became resources of resistance. They focused on the underdog, the small spider or rabbit, turning the tables on powerful adversaries using brains rather than brawn. From these tales listeners learned ways to test the power structures of the plantation regime.

In West African tales, in particular those popular among the Asante of Ghana, Anansi was a mediator between the world of humankind and the world of the Sky God, Nyame. Through his devious tricks Anansi, often inadvertently, brought things down to earth from the divine realm; stories, diseases, serpents and wisdom. In the stories told by enslaved Africans in Jamaica, Anansi himself came down to earth; in his physical form he adopted human characteristics as he became more man and less spider and pitted his wits against Tiger rather than the Asante god Nyame. It was in the plantation context of captivity and conflict that Anansi took on renewed roles and functions. Instead of functioning as a tester of the chains, Anansi helped to break them. He shifted from being assimilated into the sacred world of the Asante to become representative of the human condition of the enslaved.

Although Anansi’s interactions with the Sky God Nyame all but disappeared in the Jamaican tales, he continued to represent aspects of the African spiritual world at wakes or ‘nine-night’ ceremonies. Originating in Africa and practiced throughout the plantation period, the nine-night ceremony lasts nine nights, during which visitors spend their time singing, dancing, drinking, eating and telling Anansi stories (Perkins Ms 2019). Anansi tales are told at nine-night to ensure that the spirit of the dead does not rise and pester the living and to help the departure of the duppy (ghost or spirit) to the other side (Herskovits, The New World Negro 182).

Ar’n’t I a Woman!, exhibition installation view with Anansi in the background, 2022. Courtesy the artist and The New Art Gallery Walsall. Photo: Mark Hinton.

Anansi: Trickster Spider at the Cultural Crossroads1

In this way Anansi continued to be a crossroads figure in Jamaica, evoked during celebrations of the crossroads between life and death, the realm between gods and humanity. Representative of ambiguity, of journeys, travel, liminal states, and multiple possibilities, the crossroads played an important symbolic role in the folk practices of Jamaicans. Traditionally, on the final night of a nine-night ceremony the mourning procession walked to the nearest crossroads and performed a ritual enabling the spirit of the deceased, described in their final hour as “travelling,” to journey on whichever path they chose. Following this ritual, the deceased’s home was cleared out and mourners returned to the crossroads where they disposed of the deceased’s clothing (Chevannes 6).

The Anansi we find in Jamaica is more aggressive, violent, and ruthless than his Asante counterpart. Many elements of plantation life enter the tales, such as Massa, the whip, and the cane fields. While in the Asante Anansi tales there was a testing of limits, there were also always signs of the enforcement of community rules; this was not always the case in Jamaica: in his plantation setting Anansi could invert the social order without paradoxically upholding it. On the Jamaican plantations, Anansi had the potential to serve as the destroyer of an enforced and abhorrent social system rather than challenging the boundaries of a West African society whose members were generally compliant.2

1 Parts of this essay draw from the following book chapter. It can be accessed online for an extended discussion of Anansi’s role in both West Africa and the Caribbean: Zobel Marshall, E. (2010) ‘Anansi, Eshu, and Legba: Slave Resistance and the West African Trickster’ (2010) in Hoermann, R. & Mackenthun, G. (eds.) Bonded Labour in the Cultural Contact Zone: Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Slavery and Its Discourses (Waxmann).

2 The incorporation of aspects of Jamaican plantation life in Jamaican Anansi tales can be examined in key collections recorded and compiled by Walter Jekyll, Jamaican Song and Story: Annancy Stories, Digging Sings, Dancing Tunes and Ring Tunes (1907); Mar- tha Beckwith, Jamaica Anansi Stories (1924); Louise Bennett, Anancy Stories and Poems in Dialect (1944), and other collections from 1966 and 1979; Philip Sherlock, Anansi and the Spiderman: Jamaican Folk Tales (1956), and other collections in 1959, 1966, 1989; and Laura Tanna, Jamaican Folktales and Oral Histories (2000).

Play Fool to Catch Wise: Jamaican Anansi

In Jamaica Anansi’s predominant character traits are those of cunning, greed, lewdness, promiscuity, slothfulness, and deceit. Anansi was the embodiment of the Jamaican proverb, ‘play fool to catch wise’ – pretend to appear less intelligent than you really are to gain an advantage over those in power. The Jamaican Anansi tales tell of how Anansi, the small spider, gets the better of powerful animals such as Tiger and Alligator or commanding white humans like Massa (master), the King, Buckra,3 Preacher, and even Death. We find Anansi escaping the whip, tricking Buckra, stealing Massa’s sheep or daughters, ambushing armies, killing the preacher, playing drums, and working on his provision ground. As Jamaican sociologist Barry Chevannes explains, Anansi tales told on the plantations reflected and inspired the trickster tactics the enslaved adopted to outmanoeuvre their white masters.

Anansi became the symbolic focus of the resistance in the minds of the Africans. He was used to provide them with resilience and with modes of escape. In the plantation context he figured as a survivor. So the stories reinforced the principles of deception, guile, tek kin tit – take a smile to cover the pain in the heart, so you do not allow your enemy to see that you are suffering. (Chevannes, Personal Interview 2005)

The Jamaican story From Tiger to Anansi (1956), demonstrates the way Anansi had the power to overturn the structured hierarchy of his environment. The story starts with Tiger being introduced as the strongest animal of the forest and Anansi as the weakest:

At evening when all the animals sat together in a circle and talked and laughed together, snake would ask:

‘Who is the strongest of us all?’

‘Tiger is the strongest,’ cried Dog. ‘When Tiger whispers the trees listen. When Tiger is angry and cries out, the trees tremble’.

‘And who is the weakest of all?’ asked Snake.

‘Anansi,’ shouted dog, and they all laughed together. ‘Anansi the spider is the weakest of all. When he whispers no one listens. When he shouts everyone laughs’.

One day, the weakest and the strongest animals of the forest come face-to-face, and Anansi asks Tiger for a gift; for all the stories told in the forest to bear his name. Tiger likes the stories and wants to keep them as Tiger stories, so he sets Anansi a seemingly impossible task – to bring Brer Snake to him alive. Once Anansi has completed the task, by using Snake’s pride against him ‘never again did Tiger dare to call these stories by his name. They were the Anansi stories ever after, from that day to this’ (Sherlock,10).

Jamaica has a long history of rebellion and resistance, and the defiant attitude and resistance methods of Jamaican enslaved people are represented in their folktales. As Lawrence Levine argues, the enslaved in the Americas devoted “the structure and message of their tales to the compulsions and needs of their present situation” (Levine 90).

[Animal trickster tales] were not merely clever tales of wish-fulfilment through which slaves could escape from the imperatives of their world. They could also be painfully realistic stories which taught the art of surviving and even triumphing in the face of a harsh environment. (Levine 115)

Evidence of the ways in which trickery could be used as a method for outmanoeuvring whites on the plantation can be found in the journals of Matthew Lewis, author of the British Gothic novel The Monk (1796). In 1812 Lewis inherited two plantations in Jamaica and kept a detailed diary of his time on the island. In addition to descriptions of the enslaved telling Anansi stories, his journals record his frustration with the behaviour of the enslaved on his plantation as they find ingenious ways to avoid work and improve their conditions. 4 Plantation production on his estate falls dramatically, yet when Lewis broaches the topic, he explains, his enslaved workers always have a story for him. They will sympathize profusely with his problem and “having said so much, and said it so strongly, that he, convinced of its having full effect in making the others do their duty – thinks himself quite safe and snug in skulking away from his own [work]” (cited in Burton 57).

3 Buckra,” also spelt “Backra,” meaning white master or boss, is derived from an African word, mbakáre, meaning in Ibo “white man who governs” (Cassidy and Le Page 18).

4 Lewis records what he calls “Nancy Stories” and “Neger tricks” in his journal, some of which are told by the “picturesque” storyteller Goose Sho-Sho, “with her little sable audi- ence squatted round her” (Lewis 194, 254).

Woven Bodies 1, 2020, (detail), 548 x 630 cm, hessian sacks, screen prints, branding, animal suture thread, cowrie shells, 3D printed spiders. Courtesy the artist.

Anansi Lives On

In 2001, I spent three months in Jamaica on a PhD field trip collecting and researching Anansi stories. When I mentioned my research, most people would invariably launch into their favorite Anansi story, whether we were at a bar, in a taxi or in the street. One of my interviewees was so enthused by my research that he recorded and transcribed Anansi stories told by people his neighborhood in Saint Thomas and presented me with a handwritten collection of around a dozen tales. All this was testimony to the fact that the tradition is still very much alive in the Caribbean.

Caribbean storytelling played an important role in my own grandfather’s life. My grandfather grew up on the island of Martinique in the French Caribbean. The legacy of enslavement and colonialism was still strongly felt on the island and he seemed destined to cut cane for the white Martinican bosses. His grandmother was adamant that his life would not be spent in manual labour and worked hard in the cane fields to save enough money to send him to school and then college.

My grandfather’s novel, La Rue Cases Negres or Black Shack Alley (1950), (which was adapted into an award-winning film ‘Sugar Cane Alley’ in 1983), is based on his childhood experiences in Martinique. He writes about the folktales, riddles and oral history told to him when he was a boy by old plantation worker, mentor and griot [storyteller] Monsieur Medouze, who also raises his awareness of the injustices of the colonial regime. Monsieur Medouze uses a call–and-response technique, to make sure his audience is alert and listening carefully. ‘E-crick!’ Medouze shouts, as his begins his story, to make sure he is paying attention, ‘E-crack!’ my grandfather responds. He then tells him the story passed down from his own father, who was once enslaved, during the time of abolition:

‘I danced with joy and went running all over Martinique but when the intoxication of my freedom was spent, I was forced to remark that nothing had changed for me nor for my comrades in chains. I remained like all the blacks in this damned country: the békés kept the land, all the land in the country, and we continued working for them. The law forbade them from whipping us but did not force them to pay us our due’ (Zobel, 32).

On plantations in the Americas, storytelling was a communal activity. It brought the group together in the evening as the skies darkened. Through storytelling members of the enslaved community of all ages could rest, away from the back-breaking work and incessant cruelty of the plantation, in the company of others. For enslaved people born in Africa, the sharing of stories would have also functioned as a reminder of home. They could also work out how to incorporate the tricks of Anansi into their daily lives to resist the conditions of their oppression.

While storytelling is often associated with childhood in the UK, storytelling is far from dead. Through our use of social media we share the stories of our lives on a daily basis with our communities. Storytelling is also becoming more on trend; storytelling festivals are held up and down the county and show no sign of decreasing in popularity. We read novels avidly, we consume TV shows and films; narratives are still at the heart of our lives and central to our understanding of the world around us. We are born into stories – the stories we tell others about ourselves profoundly shape our sense of memory, identity and visions of our own futures. As we look towards a post-pandemic world, let us hope that the narratives we weave connect us together, like Anansi’s web, and gift us the strengths of intelligence, resourcefulness and resistance.

Emily Zobel Marshall

Bibliography

Burton, R. (1997) Afro-Creole: Power, Opposition and Play in the Caribbean. London: Cornel University Press.

Chevannes, B. (2001) Ambiguity and the Search for Knowledge: An Open-ended Adventure of the Imagination. Jamaica: University of the West Indies, The University Printery.

_________ (2005) Interview with author on 23 November 2005, Kingston. [Mini-disk recording in possession of the author].

Gates, H. L (1988) The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African American Literary Criticism New York: Oxford University Press.

Herskovits, J.M. (1958) The New World Negro. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

_________ (1990) The Myth of the Negro Past. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press Boston.

Perkins, L. (1910-1977) Lily Perkins Collection. Ms 2019, National Library of Jamaica, Kingston.

Sherlock, P.M. (1956) Anansi and the Spiderman: Jamaican Folk Tales. London: Macmillan.

Zobel Marshall, E. (2010) ‘Anansi, Eshu, and Legba: Slave Resistance and the West African Trickster’ (2010) in Hoermann, R. & Mackenthun, G. (eds.) Bonded Labour in the Cultural Contact Zone: Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Slavery and Its Discourses (Waxmann).

Zobel, J. (1950; 2020) Black Shack Alley. Penguin Classics: London.

Karen McLean and The New Art Gallery Walsall would like to thank;

Samera Abid; Hannah Anderson; Arts Council England; Block 336; Simon Bloor; Tom Bloor; Vanley Burke; Kaia Charles; Elizabeth Hawley; Jane Hayes-Greenwood; Josephine Hengstewerth; Georgia Hewitt; Jeremy Hunt; International Curators Forum; Alex Jolly; Sophie Kelly; Indra Khanna; Damani Lewis; Peter Lewis; Hew Locke; Frederick McGrail; Gill Perry; Richard Rawlins; Deborah Robinson; Jon Sharples; Larissa Shaw; Stephen Snoddy; STEAMhouse; Stereographic; Kevin Storrar; Jessica Taylor; Anita Veigh; Walsall Black Sisters Collective; Emily Zobel Marshall.

Karen McLean

Birmingham-based artist Karen McLean grew up in Trinidad. Her artistic practice continues to be informed by the history, culture and folklore of the Caribbean and its inter-connections with the UK.

Solo exhibitions include Blue Power/A’r’n’t I a Woman! at Block 336, London (2021), Blue Power at Ort Gallery, Birmingham (2018), The Precariat at Lewisham Art House, London (2017), three at BPN Architects, Birmingham (2014) and Trove at Edible Eastside, Birmingham (2012). Group exhibitions include MOTHERSHIP at The Sawmills, London (2016), Goldsmiths MFA show (2015), Independence Exhibition at Hackney Museum, London (2012), Trinidad & Tobago Film Festival at Medulla Art Gallery, Trinidad (2012), Trinidad & Tobago Cultural Village (2012), British Summertime 2 at The New Art Gallery Walsall and mac, Birmingham (2011) and Folkestone Triennial Fringe (2011).

Her work has recently featured in Benedita Menezes’ essay, If Eve ain’t in your Garden: Intersections between Lil Nas X, Karen McLean and Bronzino in Umbigo, #79, Lisbon, Portugal and is also discussed in Gill Perry’s book Playing at Home: The House in Contemporary Art, Reaktion Books Ltd, 2013.

Karen was recently a selector for the Gallery of Living History’s Schools Competition.

Her work has been acquired by the Soho Arts Collection.

Karen was awarded an MA in Fine Art at Goldsmiths, University of London in 2015 and BA (Hons) (First Class) at Birmingham City University in 2009.

Biography

Dr Emily Zobel Marshall is a Reader in Postcolonial Literature at the School of Cultural Studies at Leeds Beckett University. Her research specialisms are Caribbean literature and Caribbean carnival cultures.

She is an expert on the trickster figure in the folklore, oral cultures and literature of the African Diaspora and has published widely in these fields. She has also established a Caribbean Carnival Cultures research platform and network that aims to bring the critical, creative, academic and artistic aspects of carnival into dialogue with one another. Every year Emily plays mas in the Leeds West Indian carnival troupe Mama Dread’s Masqueraders.

Her books focus on the role of the trickster in Caribbean and African American cultures; her first book, Anansi’s Journey: A Story of Jamaican Cultural Resistance (2012) was published by the University of the West Indies Press and her second book, American Trickster: Trauma Tradition and Brer Rabbit, was published by Rowman and Littlefield in 2019. She also consults arts and educational organisations on Decolonial methodologies and approaches.

Emily develops creative work alongside her academic writing. She has had poems published in several international journals and anthologies. She is also Co-Chair of the David Oluwale Memorial Association, a charity committed to fighting racism and homelessness, and a Creative Associate of the Geraldine Connor Foundation.

Links to Further Resources

Links to Emily Zobel Marshall book Anansi’s Journey:

- http://www.amazon.co.uk/Anansis-Journey-Jamaican-Cultural-Resistance/dp/9766402612

- http://uwipress.com/node/29

Link to Emily Zobel Marshall’s book on the African American trickster figure Brer Rabbit: https://www.amazon.co.uk/American-Trickster-Trauma-Tradpb-Zobel-Marshall/dp/1783481102

Link to Joseph Zobel’s book: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Black-Shack-Alley-Joseph-Zobel/dp/0914478680

Link to a film version of Joseph Zobel’s book: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0086213/

Ted-Ed short animation on the Myth of Anansi written by Emily Zobel Marshall (2022): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6nWba9Ii5Lo

Block 336 showed Karen’s work in July 2021 and generated a rich range of resources which can be found here.

All images © Karen McLean unless otherwise stated. Text © Emily Zobel Marshall.