Sarah Byrne

Homebody

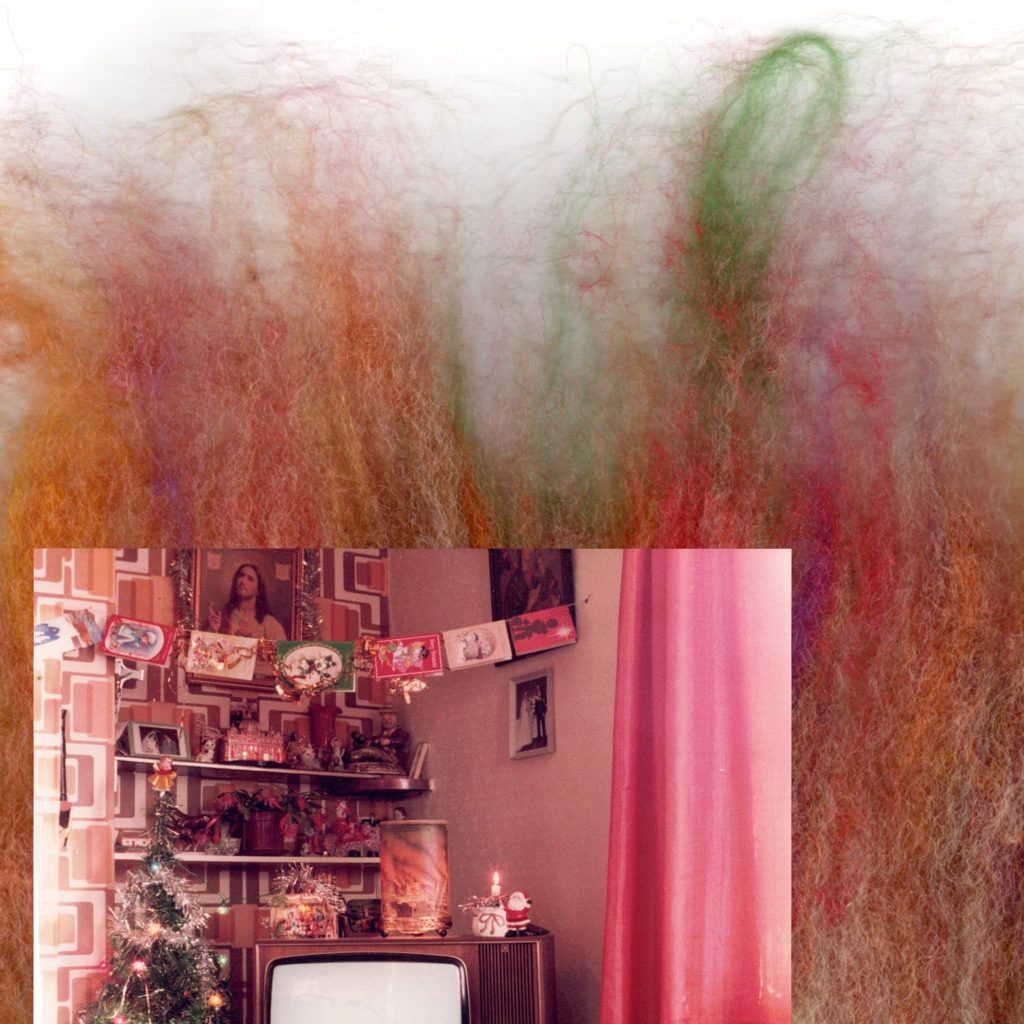

Two years on, Sarah will spend further time in the studio undertaking a new body of work focused on photographs taken by her late father. She will use the residency to explore, categorise and respond to her father’s images of holidays around Europe and his childhood home. Recently unearthed, the photographs give insight into a life before the artist was born. For the first time, Sarah will introduce crochet and weaving to the centre of her practice and experiment with dyeing and spinning yarn in colourways that recur in her father’s images.

The residency title, Homebody, is both a reference to the artist’s father, who always worked from home and was comforted by the familiar and familial, and to the restorative comfort that Sarah seeks through the work.

@sarahqueenofrat

Sarah Byrne, Artist film, June 2022

Artist Sarah Byrne talks about her residency at The New Art Gallery Walsall, sharing the photographs that inspired her studio work and her material responses to them.

Duration 5 minutes 29 seconds. Film: Mark Hinton/Blend film

As part of her residency artist Sarah Byrne posted weekly on the Gallery’s Instagram account. Below is a selection of these posts through which Sarah shared her reflection writing paired with her late father’s photographs as well as studio experiments.

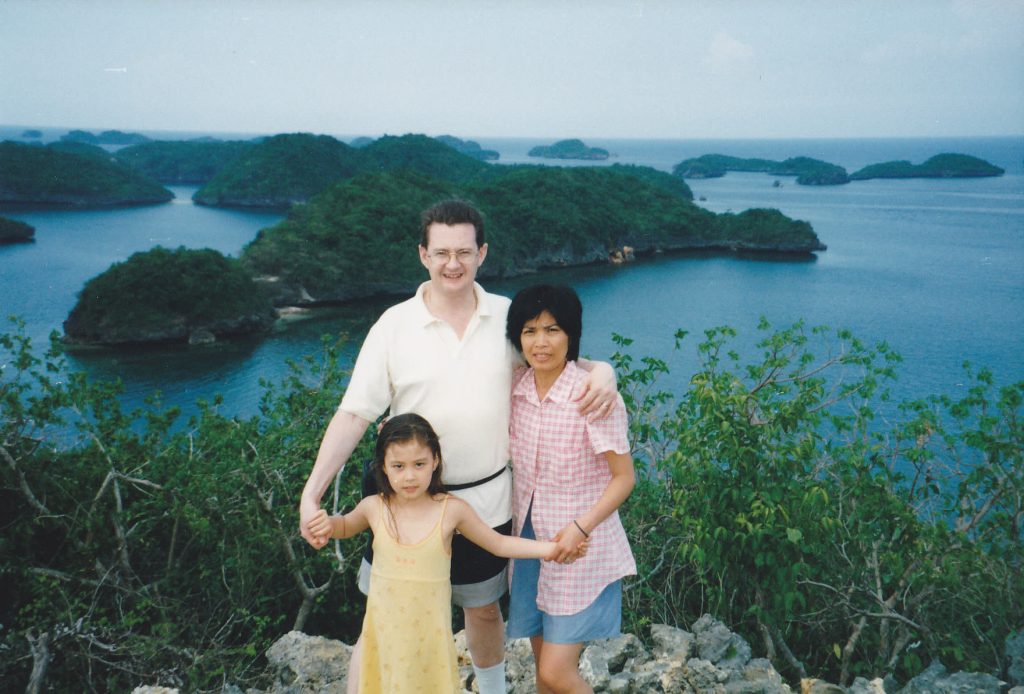

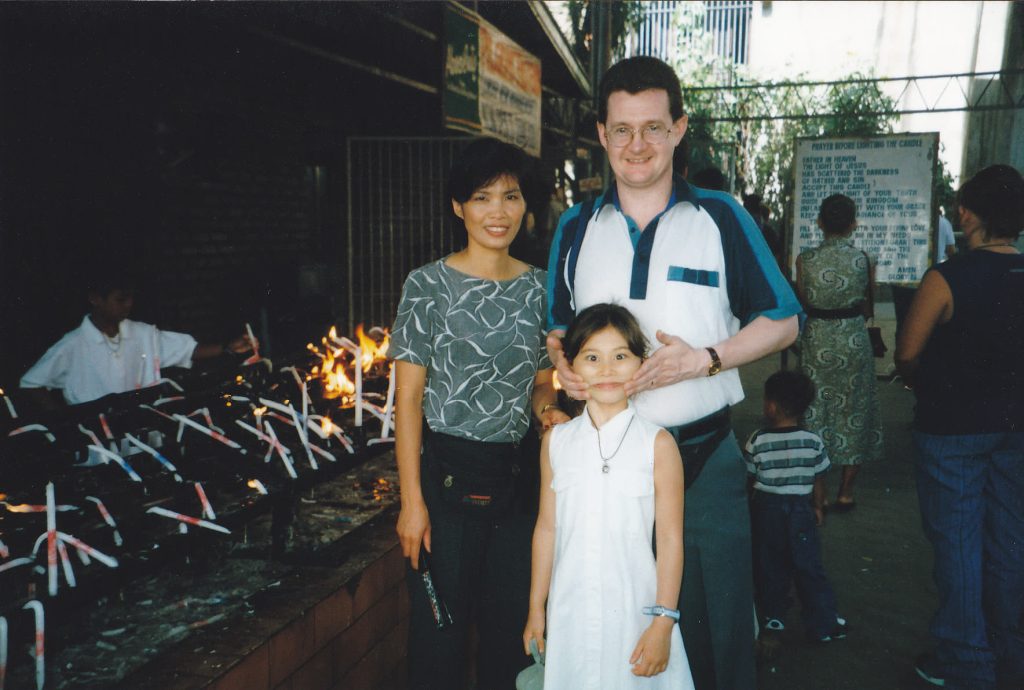

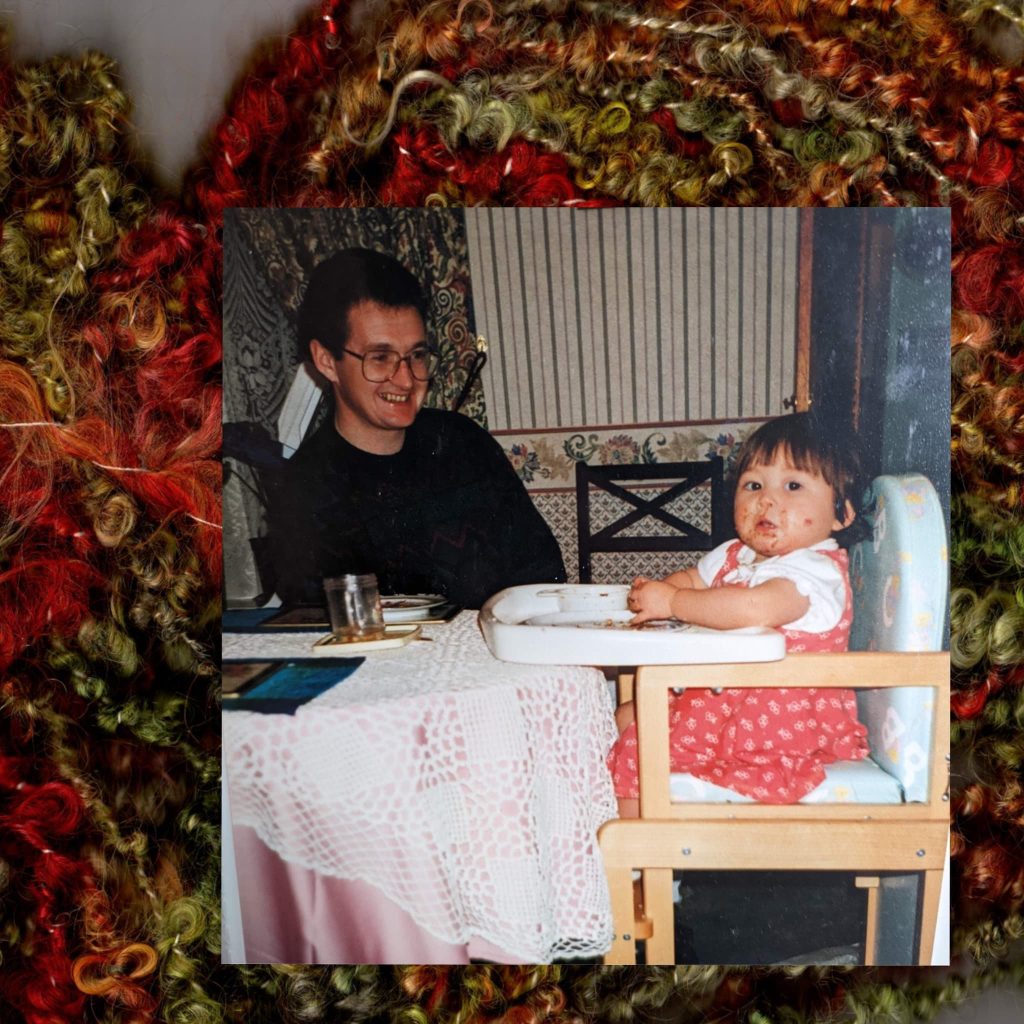

I adore family photo albums. The way they’re displayed, the order curated, the quality of the printed film photographs. In previous work, I poured over the grainy, golden texture of the ones my mum kept of my childhood, examining them and unpicking my memories around growing up between two cultures. I became obsessed by them, using them to create a narrative around my complicated experiences growing up of mixed heritage.

When my father became sick in 2020, I stopped making work. I moved in with my parents to provide full-time care while working my job online. Art-making during this time seemed frivolous, impossible. We lost my dad seven months later, and upon the slow return to my practice and discovering my new way of living, I could no longer ignore my dad’s presence in the photographs of my childhood. I felt an immediate shift – my thoughts became less introspective, and more observant of Dad’s part in it all. This was the point it became clear to me that my grief was going to touch everything. It wasn’t just something to affect my home and family – grief was a dye seeping it’s way over the fabric of my life.

Two significant things happened in 2021, in the period after losing my dad. This is the first…

Clearing up one day, my mum came across a box in her attic full of old film photographs and their negatives. At first she assumed they’d be more photos of my childhood, and handed them to me. However I quickly realised these weren’t photos I’d seen before. These photos had belonged to my dad, and largely depicted a life I’d heard about in stories but never seen. Photos taken by and of my dad in the lifetime before I was born, and before he met my mum.

Some elements I recognised: his parent’s house being the same house I visited Nana and Grandad in as a kid. The stone steps in the hedge-lined garden, the sun-soaked net curtains, and my Nana’s unflinching taste in interior décor, all sparked little jolts of memory and nostalgia like static shocks in my head. Then it all folded into a strange soup of comfort and sadness, as old memories of family and security mingled with new memories of loss.

Other photos were completely new to me, but finally gave visuals to the stories I’d heard Dad tell me a thousand times. The dinners he’d have in the houses of his University friends (where he’d unknowingly eat and enjoy a bowl of snake soup), the holidays he’d take around Europe with his cousin, the boat trip he was on where the captain threw bottles of booze into the sea for them to dive in and retrieve.

Growing up, my mum was always the primary photo-taker – the one that made us stand and smile in front of attractions, or the mantlepiece, or in my uniform on the first day of school. Dad always seemed unfussed, even peeved, by this ritual. But these photos were his. They were the things he felt were worth capturing. Funny things, beautiful things, intriguing things… These were the things that dad wanted to remember. Flicking through the stacks of film allowed me to feel his personality again when I thought I had felt all there was to feel. I was obsessed, fascinated by the knowledge that even though my dad was gone there was still more of him to discover. I hadn’t seen it all yet.

The second significant thing to happen in 2021 was this…

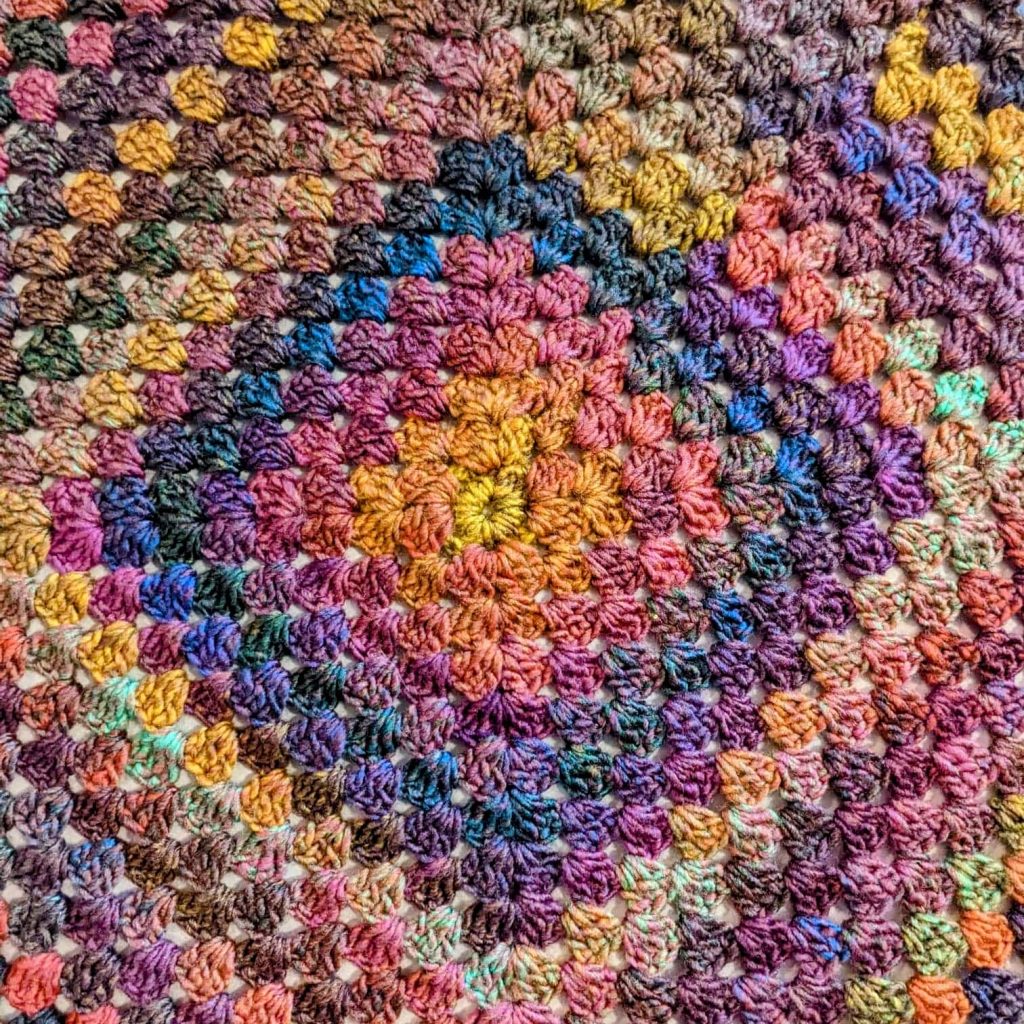

As we approached the summer, my good friend and ‘artner, Sarah Zacharek, taught me to crochet. Just one pattern – a simple granny square. This one pattern was all I could do but, unusually for me, this was a learning curve that my brain didn’t immediately drop once realising I wouldn’t be an instant prodigy. Instead, I relished the practise of it.

Loop, twist, hook, pull.

Loop, twist, hook, pull.

Loop, twist, hook, pull.

In the day, my hands twiddled with the hook and the yarn beneath my laptop camera as I logged into work meetings, and in the evenings, as my peripheral vision binged Grey’s Anatomy, my hands were still occupied. Later it would follow me to bed, where I’d lay with the lights dimmed “just finishing this last row”, remembering that I hadn’t put a wash on or emptied the dishwasher.

Loop, twist, hook, pull.

Loop, twist, hook, pull.

I started collecting different types of yarn, just as enamoured with the yarn and the colours themselves, than with any ‘made’ piece.

I hadn’t learnt yet how to join the individual granny squares together, but it didn’t matter. My pile of granny squares grew taller, and with it a sense of ambition to keep it going.

Loop, twist, hook, pull.

My hands being busy meant that my head wasn’t. As if the muscle memory stole just enough attention from the brain for its thoughts to stop circling, escalating, deafening.

Loop, twist, hook, pull.

All the while, I was also spending time examining my dad’s photographs – saving the scans to my phone, unpicking the details, observing the colour palettes.

It took me a long time to realise, but I began to wonder whether my crochet fixation was perhaps me responding to my grief and my dad’s photographs in a physical way. Whether the two events perhaps weren’t the disparate things I’d assumed, but actually two actions in direct dialogue with one another. Two compulsions, each feeding and encouraging the other.

On realising the growing relationship that my crochet had to Dad’s photographs, I began to consider the significance of where my crochet practice took place – mostly at home, mostly from the sofa, sometimes from bed. Always surrounded by comfortable, familiar security; the nest I’d created for myself.

I’ve always been a homebody, always preferring to stay home than be out. Lockdown living suited me, giving me an excuse to embrace my hermit lifestyle.

When I was growing up, my dad always worked from home. This was significant for me, for the simple reason that my dad was always around, always close by. We were homebodies together. He would escape the desk in the afternoons to meet me at the bus stop after school, and when he logged off for the day we’d dunk biscuits in tea together while Noel Edmonds bantered with The Banker on the telly. Mum wouldn’t be home until later on, so Dad and I would cook our ‘golden dinners’ together in the evenings. These were meals mum wouldn’t appreciate, but we loved; oven chips, Birds Eye chicken pies, baked beans… all golden, see?

Home was important, and it was safe, happy, comfortable. In the wake of the pandemic, these were all feelings that we felt universally hungry for – ironically despite being confined to our homes. It’s these feelings I associate with home that are so widely valuable. So when I attended the ‘Studio Escapes’ studio residency at Wolverhampton School of Art in August 2021, the meeting of like-minded hungry artists birthed one of the most restorative, healing weeks that many of us had felt in a long time. We came together during that week, relishing in the joy of sharing spaces again. From sound baths and incense, to cooking and sharing, we bonded over our need to create and share. We laughed, we sang and we sought refuge in each other and the safe space we’d created.

As well as my relationship to home, another important theme developing in my work is time. The repetitive, slow activity and the resulting collections of granny squares became a physical representation of my time spent. Time spent not only making, but reflecting, remembering, grieving, and healing. The growing stacks of crocheted yarn becoming not just pieces of textiles, but a physical token of real time.

Using your hands to make is inherently slow, as is learning a new skill. But the part I am relishing is the process of getting there. David Gauntlett describes it as ‘the satisfaction of making sense of being alive’. Which, as I sit staring into Dad’s photographs pondering loss and life, is fitting.

Distracted by this process and the accompanying reflections, it was an appropriately slow realisation for me to recognise the significance of the colours I was working with. Once I’d learnt to crochet, I started buying and collecting more and more yarn to pursue my fixation. Throughout this spree, I found myself seeking out rusty, dusty, earthy colours. Lots of deep reds, oranges, leafy greens with soft pops of mustard. These were colours that felt comforting to me and that I wanted to physically wrap myself in. I didn’t realise until some time later that these were the same colours as those repeating themselves in my dad’s grainy pictures of home.

So my next thought was to question how I could refine this relationship further. The commercial yarn I was obsessively buying was lovely, but it was fixed; I couldn’t alter it’s existing state. What if I were to go further back into the life-cycle of yarn though? Pre-yarn yarn. Natural, naked, woollen fibres; a clean slate for me to paint my colours into and spin together, forming bespoke bobbins of photographic yarn.

Taking this step into learning the dyeing and spinning skills to create my own yarn was what solidified the thought process for me that these two separate parts of my life could come together within my art practice. But from a very basic level, I’ve really enjoyed taking crochet – a recognisable, relatable activity – and framing it in the context of contemporary art.

As part of this venture, I have become a member of a spinning, dyeing and weaving Guild (Stafford Knot Spinners). Since joining this community I’ve met so many generous makers with so many years of experience to share. For a newbie like me, this has been an incredible experience of peer learning and mentorship. There’s something generational and sacred about craft making like this, and while we sit spinning away in the village hall, sipping tea and sharing biscuits, there’s a sense of strength in the community, something honest and pure about a genuine love of the craft and material. And yet makers like this may still see themselves and their work as something quite foreign to a contemporary art gallery.

During my artist residency at NAGW, I have been thrilled to speak to so many visitors who come by the studio and talk to me about my practice and their relationship to the materials I’m using. And that has been key for me; that there almost always is a recognition or a resonance that the viewer has. It’s a familiar thing – familiar visually and familiar in terms of the making. Memories of family members or attempts at learning their own crafts are discussed, and people lean in to the feeling of relatability.

I’ve never sat well with the idea that contemporary art can be seen as ‘high end’ in comparison to the craftsperson’s ‘low end’… That there’s a hierarchy between homely hobbies and gallery ‘art’. What separates them, really, other than positioning and context?

As I’ve been experimenting with dyeing the colours of my yarn fibres in response to my dad’s photographs, I’ve been keen to explore the idea of what might be considered ‘low end’. There are ways of dyeing yarn using acid dyes, requiring PPE, preparation, particular equipment, knowledge of temperatures, of exposure… But there are also lots of things around the home that can be used to stain, and I’ve been enjoying playing with these elements as a low-tech method, achievable by anyone with some old pots to dunk their fibres into.

Studio event

Lounge

Saturday 16 July 2022

Drop-in, 11am – 4pm

Join artist Sarah Byrne for some collective making in the studio, bringing along your own craft interest to make and chat in a calm and supportive environment. Participants are encouraged to engage in a dialogue about the craft they have brought with them, sharing stories about when, how, and why it became important to them.

Lounge relates to the themes of grief and slowness arising from Sarah’s residency work, where she has held traditional craft making under a contemporary art lens. Working with crochet, fibre dyeing, spinning and weaving, the work focuses on a series of photographs taken by her late father.

Refreshments available.